di Vittorio Pizzigoni

Stirling’s works during the Sixties shows an openess that other projects don’t have. Stirling was trying to find his own way in architecture, making this one of the most interesting periods in his career.

In 1964 Stirling ended his partnership with James Gowan, set up an independent office, and started some very personal research taking and testing various directions in his work. He collaborated with many different architects such as Arthur Baker, Roy Cameron, Edward Cullinan, Leon Krier and Michael Wilford. In 1971, after six years of indipendent practice, Stirling set up a new partnership with Wilford, the old collaborator of Stirling & Gowan, and occasional collaborator of Stirling during the Sixties. From this point on Stirling’s architecture follows a straight line discarding the rich possibilities experimented during the Sixties.

Among Stirling’s productions of the Sixties there are three red-brick university buildings that, at first glance, can be viewed as similar from a formal point of view: the Engineering Building at Leicester (1959-63), the History Building at Cambridge (1964-67), and the Florey Building at Oxford (1966-71). These three buildings feature large brick or tile façade; large enclosure composed of panes of glass; and the same stair-towers with chamfered corners: all these elements have been read as a reinterpretation of mid-19 Century English Gothic Revivalists. [1] But these similarities are only superficial. The three red-brick buildings show Stirling’s evolutionary process from the strict separation of functions that Pevsner recognized in Leicester, to a condensed object detached from the context, as in the Cambridge project which changed its position and orientation between design and construction, to a more unified building that finds its fixed location in the city. [2] In order to understand Stirling’s research of the Sixties more deeply it’s possible to concentrate one’s attention on the Florey Building: one of Stirling’s key projects surprising for its combinations of attention to human needs, its cryptic use of historical allusion, and its creation of a popular symbol.

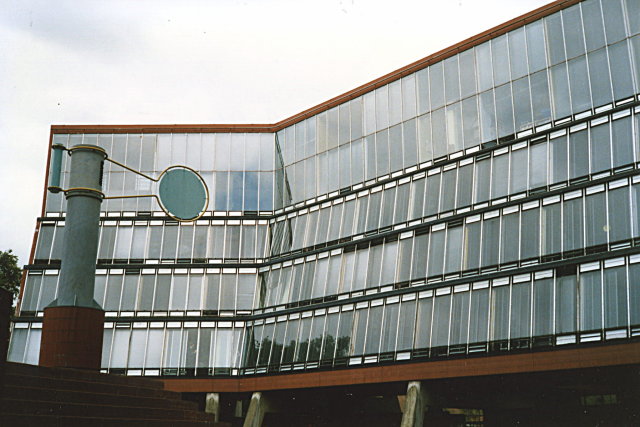

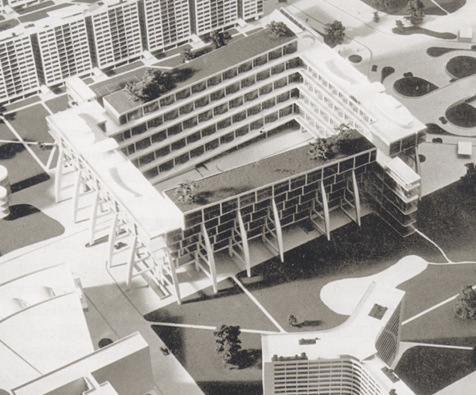

The Florey Building of Queen’s College in Oxford is, as Stirling explains, a new undergraduate residence ‘planned round a court – 120 feet across and 85 deep – which is open on the north side to embrace a view of the river and the line of trees on the opposite bank’. [3] All the residential rooms are open on the courtyard and only a few face directly north. On the outside runs a corridor from which rooms and services are accessed. There are no residential rooms at ground level and ‘a cloister runs around the court’. [4] The entrance on the south side is marked by two stairs towers, detached from the building and ‘positioned on the axis of the approach from St Clement’s Street’. [5] Alongside the entrance there is the porter’s office. A portion of the court is elevated, granting a wide panorama along the river, and under this area there is the breakfast room that can be transformed into a study or conference room. A second entrance gives access via a ramp from the cloister to the river.

The first peculiarity to consider in Stirling’s architecture is his interest in the human being, which is his greatest debt to Alvar Aalto and to the modern, north European tradition. From what Aalto called the ‘human factor’ Stirling learned to organize spaces according to visual perceptions and people’s movements, and to articulate details with attention to their aspect and use, as happened also in the Florey Building, in the design of his handrails, in the planning of meeting areas in the corridors, in the composition of the views one could have entering the building or eating in the canteen. But while these peculiarities can adequately explain the building’s spatial organization, they tell us little about the architectural decisions relating to form.

With regard to this point, it’s more important the neverending quotation process through which Stirling reuses any piece of the architecture of the past in his projects untroubled by their origin. Stirling learnt this process from his university teacher Colin Rowe. Indeed, Rowe used to play a game with his students in which everyone had to add a piece of a plan of a different building on white paper, resulting – at the end of the game – in a new plan composed from quotations of different sources. Stirling was tempted by this freedom with respect to history, and by Rowe’s predilection for Mannerism, and maybe this predilection, as his old friend Robert Maxwell remembered, was even the theoretical structure of Stirling’s work. [6]

Due to this tendency for playing with history Stirling preferred to choose cryptic and difficult rather then predictible and explicit quotations: a bent similar to that of Stirling’s very good friend Reyner Banham, the architecture critic and historian. Joking with Banham, Stirling asked him: ‘If you are a historian, find my quotations!’ [7] If one plays this game briefly, one can easily find formal echoes with the work of Le Corbusier, Aalto or Melnikov, but it’s much more difficult to find a single specific quotation.

Before the Sixties Stirling’s use of history was not completely refined, and after that period the referencing of other architectures are remixed in a totally new way, changing the relation between quoting and inventing. For this reason it is only possible during the Sixties to see Stirling’s quotation process clearly: for example, in St. Andrews residences some reference to Hannes Meyer’s project for the Arbeiter-Bank in Berlin can be find, or in the Dorman Long Headquarter can be treached some influences of the Louis Kahn Philadelphia College of Art project, but only the Florey Building assumes another project as a real model, making it unique in Stirling’s work.

In fact the Florey Building is nearly identical to a project by Marcel Breuer and F.R.S. Yorke for an unrealized ‘Garden City of the Future’ designed for London in 1936 [ill. 1]. The two projects have some astonishing similarities: the concrete trestles, the inward raked volume, and the section are the same. Furthermore, Stirling’s preliminary sketches show a rectangular court, as in Breuer’s project [ill. 2]. After choosing Breuer’s project as his model, Stirling starts to wrench it and to adapt it to people’s movements, to the conditions of the site, and to the views. Only when the overall idea is fixed does Stirling concentrate on more detailed solutions: the kitchen chimney at the centre of the court becomes a sculpture; the rail of the terrace becomes a giant element; the difficulties in cleaning the innercourt glass façade led to the introduction of same small indentations on which lean the cleaners’ ladders.

But at the core of Stirling’s work is the will to construct a symbol easily accessible and understandable to everybody. As Stirling underlined: ‘it was intended that you could recognize the historic elements of: courtyard, entrance gate towers, cloisers; also a central object replacing the traditional fountain or statue of the college founder. In this way we hoped that students and public would not be dis-associated from their cultural past. The particular way in which functional-symbolic elements are put together may be the “art” in the architecture.’ [8]

Those three qualities – human necessity, Mannerist quotation, and popular symbol – are present in equal measure in all the projects of the Sixties and in the Florey Building may be found in their strictest relation. From 1971 Stirling choose to underline the symbolic aspect of his architecture. Althought discarding the rich possibilities contained in this carefully balanced mixture of his work in the Sixties, this decision gave him a useful set of tools to engage directly with the new postmodern era.

NOTE

[1] Mark Girouard, ‘Florey Building’, Architectural Review (nov. 1972), pp. 266-8, 277.

[2] Cfr. Reyner Banham, ‘History Building, Cambridge University’, Architectural Review (nov.1968), pp. 329-32.

[3] James Stirling, ‘Florey Building for Queen’s College, Oxford, Architect Report’, Lotus 6 (1969), 152-161.

[4] Ibidem.

[5] Ibidem.

[6] Robert Maxwell, James Stirling, Michael Wilford (Birkhäuser Verlag, Basel-Boston c1998).

[7] Reyner Banham, ‘Stirling elude the hobbits’, New Society 70 (oct 4th 1984), 15-16.

[8] James Stirling, ‘Methods of expression, and materials’, in Architecture and Urbanism (feb. 1975), p. 89.

Testo in italiano Il Florey Building: un progetto centrale nell’opera di James Stirling

10 dicembre 2009