di Guglielmo Bilancioni.

Everybody knows this is Nowhere

Everybody seems to wonder

What it’s like down here

I gotta get away from this day-to-day running around

Everybody knows this is nowhere.

[Neil Young]

Built at the junction of the impossible with the available, or of the possible and the enchanting non-existent, fantastic architecture is the serious game of projection between iam and nondum, the already and the not-yet, between something that has always been here and something that, almost certainly, will never exist. In terms of Myth: things which, as Sallustius said, “never have been and always are”.

Architetcture is always fantastic, or else never is, because it is brought into presence, realized. Like every art, architecture gets its nourishment from its limits, it reaches a standstill where matter encounters the spirit which informed it.

Visionaries, as Focillon writes, “interpret more than they imitate, and transfigure more than they interpret”. ” They show sometimes what is most daring and free in the creative genius, a power of divination concentrated on the most mysterious domains of the human rêverie.” Their “peculiar vision deeply twists the light, the proportions, and even the density, of the sensible world”. “They do not see objects, they view, and therefore, examine them”.

A masterpiece with a high psychic resonance, Sabatino Rodia’s Towers of Nuestro Pueblo embody a philosophy of freedom, the image of human labour, and the everlasting creative tension – a real performance – towards realisation.

Two other authors mainly contribute to comprehend Rodia’s work.

Johan Huizinga in Homo Ludens in 1938 wrote: “Game, in the formal point of view, could be defined as a free action, perceived as fictitious and placed outside everyday life, but nevertheless able to completely absorb the player; an action devoid of all material interest and utility, done in a time and space that are specifically circumscribed, developed with an order and with given rules, awakening group relationships in life, willingly surrounding itself with mystery, or accentuating through disguise its weirdness vis-à-vis the usual world”.

And Roger Caillois, in 1958, in Les Jeux et les Hommes, would elaborate and deepen these thoughts: “Game is a free activity, separated, uncertain and nonproductive, and fictitious”. Here ordinary laws are suspended and a special awareness of a second reality, or a complete unreality, rises up.

Competition, Alea – which actually was a dice – simulation and vertigo are the keywords of the Caillois’s study, which perfectly encompass the enthusiastic motivations and deep endeavours of Rodia’s venture. Anarchic and complex, mimic and heroic, Rodia’s gesture is a true ludus metamorphicus, a surreal brilliant disguise, and a fated symbol of a one man’s will. In-lusio, being-into-the-game, is the origin of any built form, and the game, as Eugen Fink points out in The Game as World Symbol, is the most solemn among decisions. Echoes of Nietzsche in the great paradox which gives nerve to every aphorism: “I know of no other way of coping with great tasks, than play.”

Thence, the Towers are a serious play, inspired and mystical, a sacred dramatic representation. A Theatre of the World and a Praise of Folly.

Thus operated Raymond Isidore, called Picassiette, “Dishbrake”, at Chartres, Ferdinand Cheval, le Facteur, the Postman, in his Palais Idéal at Hauterives, Pirro Ligorio at the Rometta, an ancient Rome in miniature, in Tivoli, Vicino Orsini in the Holy Wood in Bomarzo, François Nicolas Henri Racine de Monville at the Désert de Retz, Tomaso Buzzi at La Scarzuola, Niki de Saint Phalle at the Giardino dei Tarocchi. So did Tressa “Grandma” Prisbrey at the Bottle Village in the Simi Valley. Castles made of sand.

A special mention is due to Gaudì. But Rodia scaled him down: somebody helped him, as he said. Like all the other follies these works exalt the non-material aspects of the art of building, and overcome the limits of the so-called ‘function’. And, while creating disconcertment and confusion, they highlight on the iconological program, and on Pathos towering above Ethos, understood as usual dwelling. These quirky and funny yet involving masterpieces, with their calculated fusion of archaic and modern, their granular character, their never-finished aura, their rusty folksy tracery, perform in their plastic florescence an insatiable craving for beauty. Bizarre and sublime secret places, where “past is a foreign country”, as Leslie Poles Hartley said: “they do things differently there”. David Lowenthal drew on the sentence in a title of one of his books, and added: “they speak a different language there”.

Sumptuous and non productive, antropomorphic and teratomorphic, the Watts Towers are a building from Elsewhere, late-antique and nostalgic, transient and ephemeral, made out from enchantement and disenchantement, in the spires of which the feeling of the end is controlled by the modernity of bricolage. A bejeweled bricolage, a jewel box or a treasure chest of dreams, offered as a gift, free and for free, gratuitously.

As Dal Lago and Giordano explained very well in their book Fuori Cornice, Out of Frame, this is the noblest gesture an artist could offer.

Magic more than naïf, for genuineness and ingenuity stem from the same root, Rodia joins with courage the Opus Incertum into a new iconology, through Spolia, meaningful fragments recycled and upcycled, fractal geometry and kaleidoscope aesthetics, where symmetry and rythm override..

When asked about the meaning of his Towers, Rodia said: “They mean lots of things, son”. They could be celebration of California highways (66, 99, 101, the height of the three towers, as Rodia himself said), or a complicated sundial system, whence the sun casts a shadow from its triple style, or Gnomon, a ship of fools, or an Ark.

Paul Harris explained in a very heuristic way that the Towers are the three masts of a ship, an Ark actually, explaining them through Ronald Johnson’s poem Ark, which has a Rodia’s Tower on its cover; there the word-knots Hearth Heart Earth, joined with the cosmogonic sense of Clinamen in Epicurus and Lucretius, illuminate the free will of living things, the much in the little, and the whirling beauty of apparent casualness.

Rodia acts as a Rousseau le Douanier architect, or a new Ligabue with a Dubuffet flavor, as well as a forerunner of Ele d’Artagnan’s psychedelic cosmography. Clarence Schmidt’s aluminium foils and Jean Linard’s mosaics should also be recalled, along with Posada’s Calaveras, in this unsettling context.

Many ideas and ideals are to be found here in this spiral-like uproar: Rem Koolhaas’s Junkspace (but Jon Maidan reminds us: beautiful junk!), David Leatherbarrow’s Architecture oriented otherwise, the Mediterranean vernacular and Buckminster Fuller, Art Brut and Jazz, the débris and the Muschelwerk. And Sophia and Phantasia, wisdom and fantasy at their confluence. The Ancients called this Imaginatio Vera.

The Towers – Vortex of noise and Cathedral of Jazz, as Don De Lillo defined them in Underworld – show very well that the difference between magic and technology depend only on historical variations. And the same happens between the organic and the mechanical, perfectly modulated here and therefore homogeneous.

Magical matters and technical matters are fused here, at a very high temperature, in this sort of dream: “It’s just a dream, I wanna keep on dreamin’ it”.

Visionary machina and silent fabrica, though ringing and flashing, Rodia’s double construction, equipped with a consolding altitude connection, marks the supremacy of the skeleton over the work of art, as in Tatlin’s tower, in a giddy topology of the hollow. It is pure structure: machine à grimper and piéce de résistance. Before Tatlin the poetry of technique was found by Shukhov with his Hyperboloid Lattice Shell structure Towers, high and light as stellar baskets. The first Mnimosti – which is imaginariness – high-tech.

A bit gothic pinnacles and a bit hindu sikhara, the towers had for their builder the character of a Mandala: you have to compose it following the line of precision and you have to leave the result to the great law of the Universe. Thomas Harrison in an essay on the Towers explained this very well: “Once the structures were finished, they lost their purpose”.

Meanwhile, iron and mortar, spires encrusted with broken crockery, accumulation and inlay, and the alchemy of fusion.

Iron is used whenever power and necessity are supposed to be manifest. So, the Towers can place a panorama in the town, a mirador, and some ‘points’ of view, to see and be seen, as Le Pont des Planètes by Jean-Ignace-Isidore Gérard, famous as Grandville. For, as Walter Benjamin said, studying the origin of iron construction: “Technological production – at the beginning – was in the grip of dreams. Not architecture alone, but all technology is – at certain stages – evidence of a collective dream”.

Sabatino Rodia is a Wonderworker, craftsman of the Opus Magnum. A producer of marvels, he built a miniature of the universe, a civic temple in perpetual disrepair. This poetic acrobatic gesture of a gothic glass master, which Bruno Zevi with descriptive precision defined a “Tower of Babel made with iron wire, a Christmas tree, or a firework”, is an “Incunabulum of informal architecture”.

It’s a cloud scraper or a lightning catcher, incorporating the essence of a Nymph grotto with dome and apse; a gigantic antenna in the creative paradox of an experimental Utopia. It’s the aesthetics of Jules Verne’s flying machines and Albert Robida’s Cures d’Air, whence a precise prophecy of the past produces monuments fit for the purpose of forgetting the future, fot tempering the catastrophic and the apocalyptical, and giving back and restoring joy into vision, as for Finsterlin and the Archigram.

Rodia masters techniques, as an avant-garde artist: assemblage, collage, montage, fusion, groovy joint, in a style which encloses truth. A mirage style made of unpredictable compressions, apparent randomness, and sharp sternness, fantasy of innocence and artistic titanism, more geomantic than geometric, more archaic than modern, where the Caos of Proteus encounters the happy tangled weave of fate and cause, the order of enthropy: objets trouvès and structural joint venture. The traces left with cookie cutters are the first evidence of a pyrotechnical extravaganza, mixed with an exquisite taste for color; an exemple among all the green of 7up bottles harmoniously tangled with the blue of Magnesia Milk bottles. With an add of red jelly plasticity, mixed with stirring terracotta and steel. The spirit of quilts made in patchwork, along with the endless wire of the spiral, live in the work of the artisan-artist, whose only aim is a well-done job, “un lavoro ben fatto”, as Joseph Sciorra pointed out: “Che bella insalata!” Sabatino smoothed all the rough edges off in his italian-african-mexican mosaic work, in his spiral layers used as small steps of a stair, and stated with pride: “If you do something half good and half bad, then is no good”.

The spiral has been defined, by Jakob Bernoulli, “Curvata Resurgo“. Curved, I straighten up. This metaphor could be the araldic device of Rodia’s behaviour, curving pieces of steel with the railroad tracks, and rising up to the lonely top.

Dizziness of height, oddity of the meander, quizzical volouptuosness of danger and fabulous distance: this is Futurism, with an echo of 1888 Edward Bellamy’s Looking backward and of William Morris’ News from Nowhere, of 1891.

The solitary aesthetic hero, a self-taught Transformer, with his ‘no-pulley’ thoughts and a subtle control over the result, stages a rollercoaster vison in his vertical challenge, with a sweetly astonished serenity, primeval and sophisticated bravura, a mix of talent and courage, in the virtuosity of the one man band: one man, alone, equipped with allegorical genius and a dizzy know how. His dripping in height is pure rhetoric, a figure of speech, Blindness and insight, Paul de Man would say.

Rodia realizes, as Reyner Banham wrote, his “mechanical Satori” as surfers, hot rodders, sky divers and scuba divers do. California wouldn’t really be the same without Neutra and without Rodia.

Is Roger Caillois, again, who explains: “You must call vertigo every attraction whose effect surprises and disorients self-preservation instinct”. Here is the deepest meaning of Rodia’s strongest sentence: “You have to be good good or bad bad to be remembered.”

In the alien attitude of Rodia’s delirium lie grace and composure, wild features, pictorial enigmas and hieroglyphs of pathos, and a respectful love for Mater Materia, mother-matter with its own form; in his work can be found the “sumptuosity of the modest”, the glory of which has been described by Simone Weil.

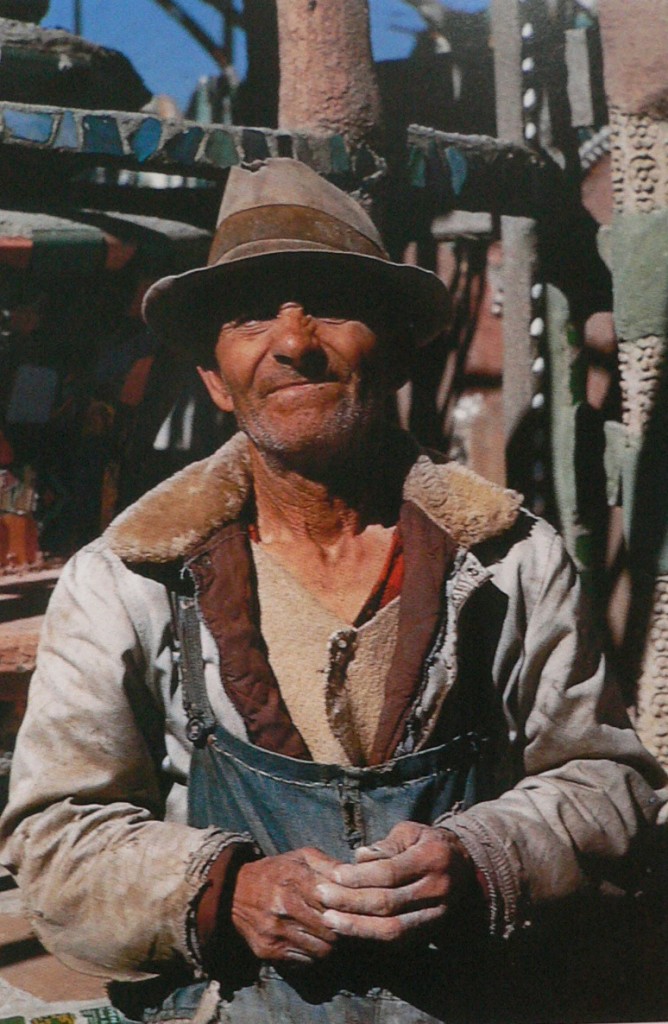

In the power of will, as grandiose as it is simple, the Superman – “I am a Steel Man” – overcomes and surpasses himself: in Rodia’s endeavour is concealed a pure expression of the Titanic in art. His Will to Art shows a state of mind where “the mountain is a cloud”, as Leonardo ‘Diobello’ Sileo, another talented pauper italian, said. I work “Solo per lasciare il nome”, just to leave behind the name. Mano mano, mano mano. Little by little, with bare hands.

As a conclusion the assessment: “I had in mind to do something big, and I did it.” It must be true: It takes a tough man to make a tender architect.

Rodia’s Hypnerotomachìa, battle of love in dream, obstinate patient and resistent, has been able to become Technomachìa a battle with utility and revelation, inspiration and calculation. His Delirious symphony is an Hymn to endurance. This spurious construction, built with non homogeneous building material is the triumph of structural form, inside of which, as in every work of art, psychic and physical forces cohabit in a restless struggle.

Sabatino has the fire inside: an afflatus which becomes matter through inexausted labour: the epic of improvement. Tools, a cathedral builder’s tools, are the loner’s best friends. A poet sang: “Chisels are calling… Steely reminders of things left to do.” Every night up, and many days up yonder with his lunch box, Caruso on the grammophone, sparks all around, lamps mounted on a bycicle wheel, chisels, rasps, hammers, pincers, lucky horsehoes, and, of course, his window-washer’s equipment.

The mysterious path that led a pioneer from Ribottoli, comune di Serino, provincia di Avellino, on the River Sabato, to set a bowling ball among Canada Dry cans, the mother-of-pearl of shells, records (imagine if he had had Cd’s…), corncobs and mirrors, in Los Angeles, California, is illuminated by the light of uniqueness, in the delicacy of a butterfly and the horny toughness of a bone joint.

Walking alone in the middle of this path, Rodia did demonstrate with proud humility that it is possible to recompose the shattered and that salvation is hidden in the Smallest.

Let me please conclude as I started: “There’s more in the picture than meets the eye; hey hey my my”.

4 novembre 2010