Interview to Denise Scott Brown

edited by Silvia Micheli

Venezia, IUAV, Badoer, Aula Manfredo Tafuri

Scuola di Dottorato IUAV

June 24th 2010

Silvia Micheli: Let’s start from Las Vegas. In 2008, at Drexel University, you and Robert Venturi were interviewed by Paula Cohen.

Denise Scott Brown: Yes.

SM: During the discussion, you spoke about the influence on your research on Las Vegas of Tom Wolfe‘s book, The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby published in 1965– strangely, the Italian translation of the bookmisses the first chapter on Las Vegas…

DSB: It may have been difficult to translate. I worked with a Roman architect in translating my“Learning from Pop“andthere were noequivalents in Italy for some American things: it wasn’t just a question of finding the right words.

SM: How did the book influence your research work?

DSB: Wolfe had an elegant spirit. We so muchenjoyed his strange, art-historical-sounding names for signs and the arcane descriptions he evolved to give a multi-layered sense of The Strip. In this article he defined a literary style that was modern and tied to life as led, but also refined and chic. With it he brewed a jarring but artistic, even gracious, mix. We enjoyed the combination. It was our own. As with Ed Ruscha, we recognized an approach similar to ours.

SM: Inhis first writings, Wolfe dealt with the habits of the masses, for example the business of the cars.

DSB: Does he say «the masses»? It’s a term I don’t use.Architects talk of the masses. During the Russian revolution M.J. Ginzburg wrote that the masses would surely agree with Modern architects on the need to drop the sentimentality of middle class icons and cultural objects. But of course they did not.

Social scientists in America now would say that we cannot usefully talk about the masses, that we need to consider the subgroups that form large populations, that even the commercial discussion of «markets» and «market segments» is better than rhetoric on the masses. And mention of the word in our profession usually carries the corollary «We the architects know the real needs of the little people».

The same goes for the “mass media”. Modern means of communication permit messages to be targeted to families, women, men, young people, intellectuals, non-intellectuals, poker players, football fans, philatelists, entomologists – there are million ways to cut the media pie. And one individual can belong to several groups. I may hold certain opinions as a woman, others as an architect, and yet others as a planner. To fulfill these roles I must internalize conflicts among them. How could it be otherwise? And should it be otherwise? When people harbour no internal conflicts they become one-dimensional and may become ideologues. That can be dangerous. Conflicts within the individual may be a valuable protection against extremism, against the possibility of another Hitler or Mussolini.

But can people be targeted at all in clusters, or only as individuals? Have you ever been in a foreign country and felt that there was a secret in the air that everyone but you knew? I felt that strongly in Italy. I believe there are big groups – regions, nations, sports fans, teachers – who can be reached as a whole, otherwise “Things go better with Coke” wouldn’t work. And if communication is one of the functions of architecture, then we architects must understand the hierarchies of messages and the forms of communication that should co-exist, at certain locations and within different building types from a city hall to a suburban house.

That is my story about the masses!

***

SM: Learning from Las Vegas is one of the most important books of the past century. It was published one year later than Los Angeles: architecture of four ecologies by Reyner Banham. In many occasions you spoke about your interest in Los Angeles. What relationship wasthere between the two books? Between the authors of the two books? At the end of the 1960s, did you know Banham’s work?

DSB: I knew him in England, but not very well. Yet I was one of the few people he allowed to call him “Peter”, not “Reyner” – I don’t know why. I’ve no more than skimmed his book. And… I’m trying to remember, I’m old and my memories are dim…

I remember a conversation we had in London, I think. He said: «The trouble with Peter Smithson is that he insists on writing». When I asked what he meant, he said: «Peter should do the design and leave the writing to people like me».

Than we lost touch and I had little contact with him in America. But in 1965, from Los Angeles, I wrote to him in London saying, «I’ve seen Las Vegas and want to write about it». I questioned him on the British «RIBA Journal». I needed colour to illustrate my slides of the signs of Las Vegas. I knew the «Journal» published in colour, so I asked if he thought they would accept an article on Las Vegas. He replied, «After Tom Wolfe, who has anything more to say about Las Vegas?» That was amusing because a few months later, Peter’s own writing on Las Vegas appeared! And his views on the city’s relevance were disproved when, in 1966, Bob and I visited it, collaborated on two articles and a studio on it, and produced a book that has been in print nearly 40 years.

SM: In fact it is hard to verify the contacts between you and Banham. So, your researches are similar but not interconnected?

DSB: Not strongly, but we shared the same era and, for a while, the same place, London. We were both interested in the New Brutalists and the Independent Group that they were part of, in Team 10, and in the times, the zeitgeist, that spawned such thinking.

***

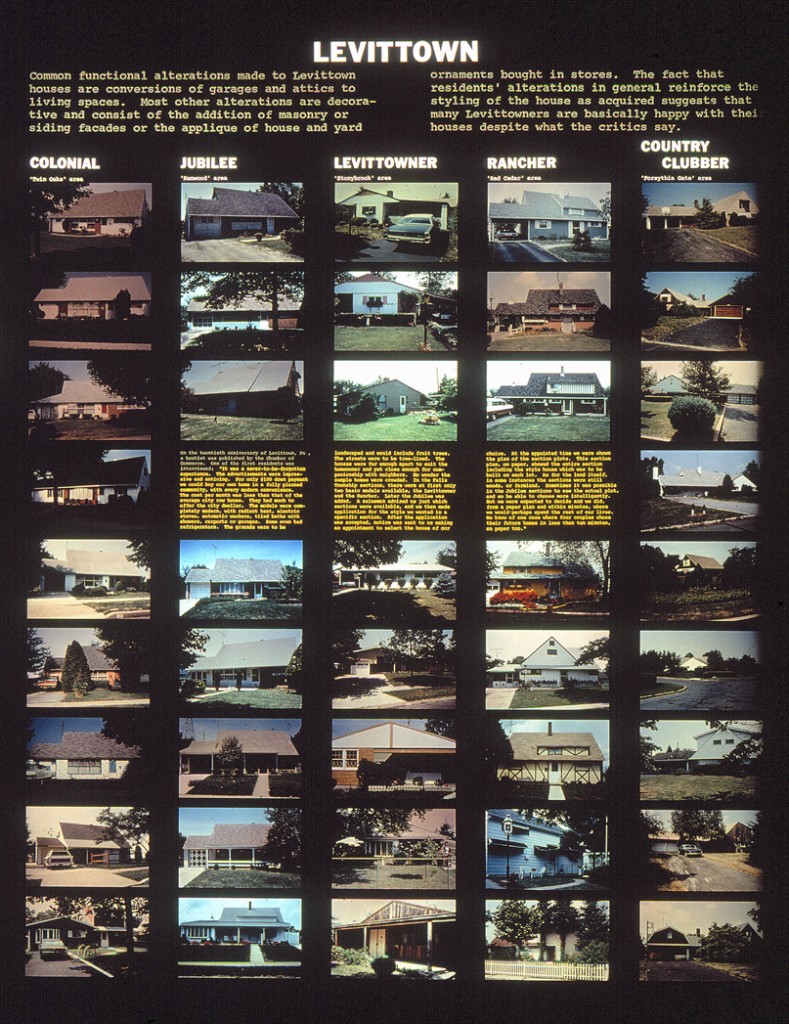

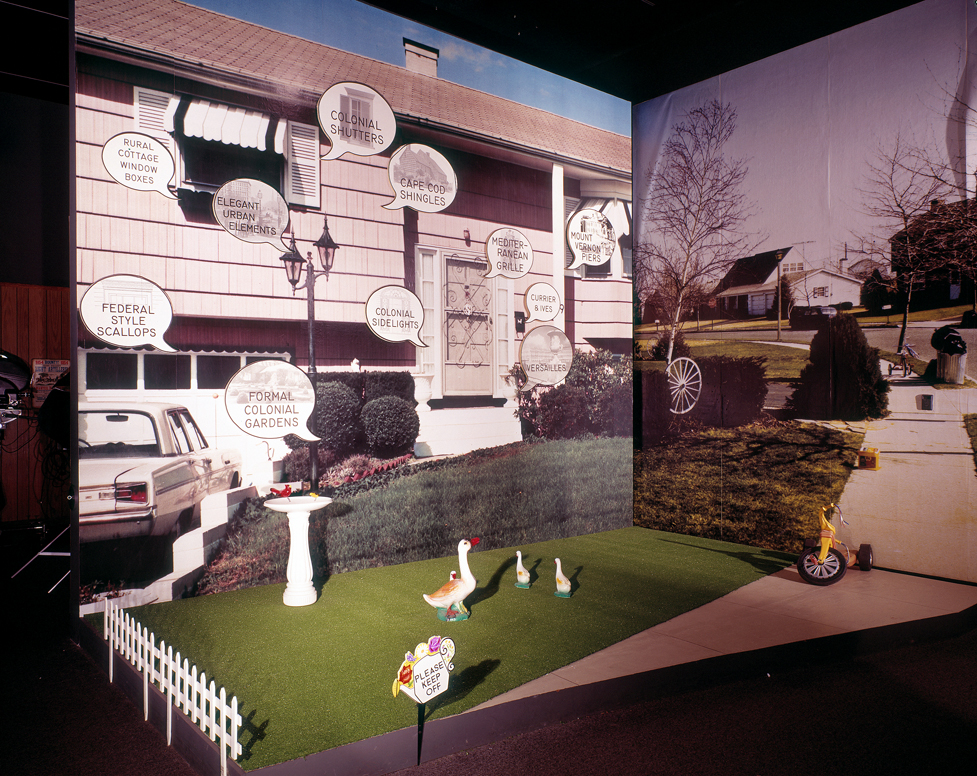

SM: The research project Learning from Levittown or Remedial Housing for Architects, led in 1971 at Yale by you and Robert Venturi, was intended to be the companion volume to Learning from Las Vegas.

DSB: Yes.

SM: Therefore it seems to be very important in your research process. Why is it still unpublished and in some way less popular than Learning from Las Vegas?

DSB: We were running a small architects’ office, but Bob and I insisted on operating a little university within it. This was expensive and our partner, John Rauch, felt the firm could not afford to publish a third book. After these studios we stopped teaching. We had had a child, but also we realized that our time spent in school should be put to looking for work – if we wanted to have a real office, not just a “start-up”. But the exhibition “Signs of Life” (Smithsonian Institution, 1976) was a form of publication.

Crown Publishers wanted very much to publish “Learning from Levittown”. «We can get it out very quickly! – they said – We’ll just publish it the way it is». But I said no. Although we liked their offer to publish quickly and cheaply, I felt they would impose their own interpretation, that the book would not be us. But he assumed I did not trust him financially, and with his good-bye handshake he said: «Make sure you still have your fingers!».

SM: I found a short text of this study in «Lotus» 9/1975, but unfortunately it is just a part of the whole work...

DSB: Yes, it’s a great shame. Beatriz Colomina’s doctoral students at Princeton University were trying to make a book of it, or perhaps a film.

***

SM: Rem Koolhaas, in a recent interview with Hans Ulrich Obrist, Robert Venturi and you (Re-learning from Las Vegas, in Content, 2004), discussed the influence of your Las Vegas study on his Delirious New York.

DSB: Yes.

SM: Do you see a methodological continuity between the books?

DSB: I don’t know his book well. For years I’ve been too busy practising architecture to read. I know Rem sees continuity between us. But he also describes our differences.

For example, Rem didn’t like the Las Vegas he analyzed, whereas Bob and I both hated and loved ours.

Although I don’t always agree with him, I admire Rem greatly as an architect and thinker. He is an engineer too, and you can see it. And like us, he is a functionalist. He is very direct – perhaps over direct. He told me that he choses what I call his “take no prisoners” approach to materials and details to meet Dutch construction cost limits, which were too low to cover refinements. But that may have been an excuse to do what he loves. His functionalism, I feel, is sometimes too blunt. He makes big, bold, passionate design decisions that derive uncompromisingly from function but that can be unfunctional in their consequences or detail.

I’ve just visited his Music Center in Porto. Some aspects are fascinating and strangely charming, but others make you think: «That can’t work. It’s a waste…».

Rem has been extremely kind to me. I’m deeply grateful for his understanding of my role as an equal with my husband in architecture. His comment on Bob and me – «There’s a really interesting tension between the two of you» – showed a rare awareness of this well-spring of our creativity.

***

SM: Between the 1950s and ‘80s there was much research on how to read the city in a new way, different from the Modern experience. Architects tried to find new methods of analysis in order to understand the structure of cities, rather than imagine a new urban design for them. Do you agree with this point of view?

DSB: Very much so. I helped to form it.

SM: Which studies did you note as most relevant during this wide and bright period?

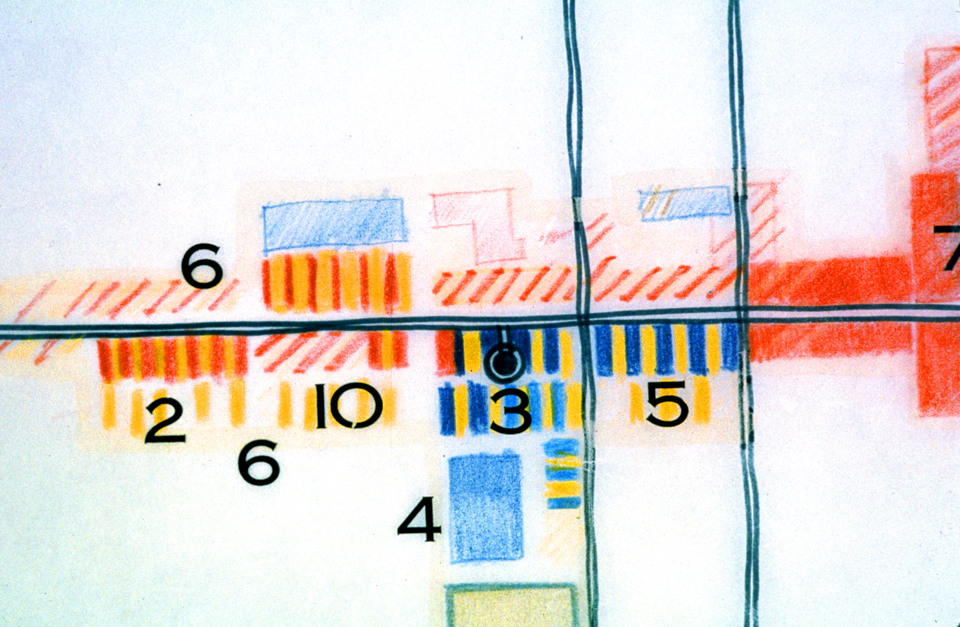

DSB: I was at that time searching for new methods of analysis and synthesis “outside” architecture – that could help architects break from their narrowly architecture-centric views. I found useful thought and techniques in urban sociology, systems thinking, Pop Art, Mannerism, and the area of land economics called Regional Science – to name a few. Even in the 1960s computers played an important role. After War World II American social scientists and planners tried to adapt war-time computer techniques to research on cities. Transportation was an early focus, perhaps because the tax on petrol (gasoline) could provide research money. Kevin Lynch at MIT and Philip Thiel in Seattle used the computer capabilities of their universities for urban design analysis. In the 1950s, a citizens’ group investigating new ideas on movement for Philadelphia, said to one of its members, «You draw better than we do, draw it up». The member was Lou Kahn, and the result was his famous streets study. And David Crane defined “The Four Faces of Movement”, as he called it. I was Crane’s student. I joined him in his thinking about urbanism in 1958 and through him I wrote my first paper on perception and movement, “Meaningful City”, in the early ’60s. But I had been doing related thinking in London (Donald Appleyard was a friend in my class at the AA) and in Europe.

***

SM: Did you learn from Italy? If yes, in which way?

DSB: Robert Scott Brown and I were in Italy in 1956-57, but my learning goes back further. I’d studied Italian Classical and Renaissance architecture in South Africa, and in the early 1950s at the AA, taking John Summerson’s course on Classicism twice. This gave me a general acquaintance with Italian historical architecture and, thanks to Summerson and the Smithsons, a particular interest in Italian and English Mannerism.

Before 1956, I enjoyed announcing that I was an architecture student who had never seen Italy. But I had caught a glimpse in 1936 when we sailed from South Africa to Europe on the Duilio. As a four year old, I heard Italian spoken and gathered my first experience of a world beyond home – of the ship and the jolly staff who cared for us. “Uno… due… TRE!” As the food went into my mouth, I learned to count in Italian. «Italian is a lovely language – said my father – you should learn it». So as a toddler I thought I should learn Italian, and 20 years later I did.

On my first adult visit I stayed almost six months. This was part of a year-long study tour Robert Scott Brown and I planned, after graduating. Starting with the CIAM Scuola Estiva of 1956, we spent two months in Venice, then travelled south eventually reaching Rome where we wintered, sight seeing and studying the city but also working briefly for Giuseppe Vaccaro. Robert and I travelled as only the very young can. We camped in fields or stayed in alloggi near the rail station. Our vehicle was an old Morgan sports car, a three wheeler. Wherever it went it caused a stir. When it broke down we hitch hiked.

Through our need to work and our broken vehicle, we were dependent on those around us in several countries. In this we were so lucky. And in the case of Italy, our involvement with people led to life-long friendships. Leda, Giuseppe and Carolina Vaccaro in particular have added major dimensions to my life, ones that Bob Venturi came to share. [1] And I know the Italian names for the parts of small English sports cars.

Bob and I have returned frequently to Italy to lecture. Year after year we travelled to Venice, bringing my mother, our small son and several of his cousins for a brief family holiday. Or we spent days in Rome in August, when the traffic is quiet, living alongside Carolina Vaccaro and revisiting favorite churches and palazzos. That’s a short version of my long history with Italy.

Bob, as an Italian American, has an even longer one. His father was born in Atessa. He immigrated to America as a child and wanted to be an architect. But when his father died he left school to run the family’s fruit and produce business. Bob’s mother’s family experienced all we hear today of poverty in American inner cities. But she grew up to be a pacifist, socialist, and well educated lady. So Bob’s family’s progress in America was not so much upward mobility as vertical take off. And although his parents were forced to leave school early, they loved Italy and architecture and surrounded Bob as he grew up with books and pictures of Rome. At Princeton, he learned to love his Italian background as an architect. Bob was a Fellow in the American Academy in Rome, 1954-56, and he still celebrates his first day in Rome, August 8, 1948, sometimes with a party of friends at Gigetto Restaurant in the ghetto.

SM: During the 1960s and ‘70s,particular attention was paid in Italy to urban analysis as an important part of the architectural project. Aldo Rossi, Vittorio Gregotti, Guido Canella and Giorgio Grassi studied the history of cities in order to understand their structure and be able to designfor the specific context. What do you think about this experience and did you know their research at that time?

DSB: Yes, I knew Rossi and Gregotti and I knew Ludovico Quaroni and Giancarlo de Carlo through the Summer School. Quaroni helped us find work with Vaccaro. But, except for de Carlo’s study of Urbino, which I reviewed, I know little of their urban analyses. However, I doubt whether our approaches were similar – the only Italian architect I know who studied Regional Sclence is Annamaria Cassini.

***

SM: Let’s come to the present. Nowadays there is a renewed interest in the city but it seems that architects don’t have the right instrument to approach the theme. What is your idea on it and what kind of suggestion could you give to the younger generation?

DSB: I began work on the ideas I discuss now in the late 1950s and I drew slides I show on urban relationships in the early 60s. Today young architects are returning to these topics. For years their parents and grandparents weren’t interested. When I said that “Learning from Las Vegas” was in part a social tract, they replied: «You’ve got to be kidding. It’s antisocial». But this generation understands that the book carries a social message and responds to thought that drove political movements of the 1960s. [2]

Architects involved in research tell us that the methods of “Learning from Las Vegas” guide what they do. The title “Learning from …” has been applied from China to Africa, and I’m happy to read my words in the work programs of their studies. Academic thinkers in the arts, social sciences and humanities are interested in LLV too, for its approach to popular culture and for what they call «the studio model» and «learning by inquiry».

But although I’m pleased that architects are now nearer to our position, there’s still far to go.

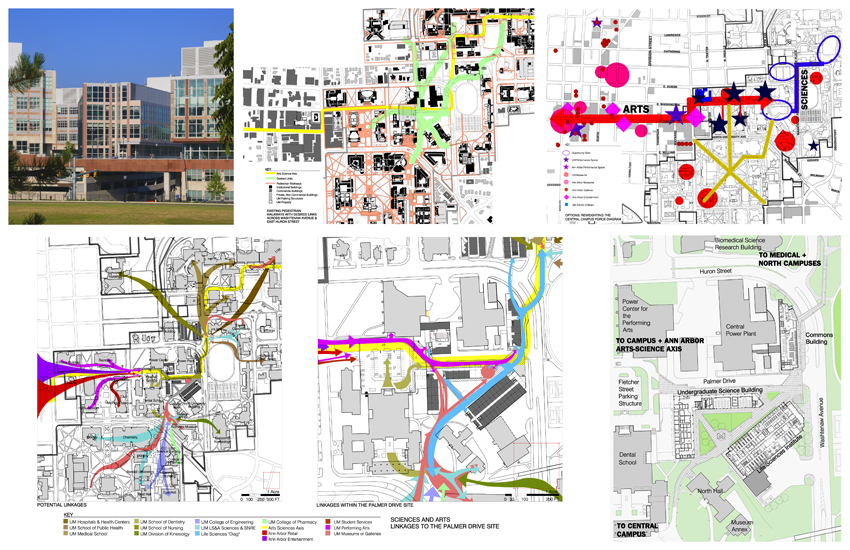

“Learning from” studies to date have appropriated only limited facets of our LLV and LLT material and techniques, and the research studio’s role within an overall education plan has not been thought through. Therefore it’s hardly surprising that architects today use urban research information for sculptural purposes – city mapping, for example, as an aid to discovering cool new forms. They ignore the relationships these maps reveal. And they miss the powerful resources offered by mapping that shows how social and economic conditions distribute “on the ground” . Architects need such information to achieve what they have long desired: ability to design what Aldo van Eyck called «the physical counterform to social form», what the Smithsons called «active socioplastics».

Since the 1960s I have worked, first as a teacher and researcher then as a practitioner, at incorporating urban information into design at urban and building scales. Our projects span from decorative arts to regional planning but most, by far, are public and institutional buildings and complexes. An urban approach informs them all. Our South Street advocacy plans and Bob’s “Mother’s House” set out our urbanistic ideas in embryo, and they appear more fully developed in, for example, the Sainsbury Wing, the Conseil General building in Toulouse, and the Life Sciences complex in Michigan. In “Architecture as Signs and Systems for a Mannerist Time” [3] we give the reasoning and intellectual history behind our work, and show how, over 50 years, we have translated into architecture the third reassessment of Modernism – the one we offered in LLV .

Today a fourth reappraisal is needed to suit “the shifting paradigm” as changing times are now called. But we can’t do it. I tell young architects that I don’t begin to understand today’s paradigm – that they are the ones who will have to work out the lessons to be learned and find their own enquiry models, using the new technologies, which they understand so well and I hardly at all.

SM: Yes, a sort of a new layer we are supposed to deal with …

DSB: … but I love my Blackberry. It lets me conduct my business wherever I am and send and receive ideas worldwide. It’s also my impulse machine that speeds love to friends and family. And it’s made as beautifully as a piece of jewelry.

***

SM: What are you learning at the moment? After Las Vegas, Levittown, Tokyo and Shanghai, what case study are you working at now?

DSB: I’m not working on one now, but in Shanghai my head filled with studies I would like to do and studios I would like to teach. I hope one day to list these – perhaps other architects might like to attempt them.

I’m thinking of the arc of our career. I’m writing the minutes, so to speak, of meetings I’ve attended – setting straight our corner of architecture, saving it from misinterpretation. [4] These concerns – a grandmother’s – are my passion now. I do it for architects who will take up the beacon of Modernism and the responsibility for discipline building in the future. I hope that those among them who share our ideas will see each other as colleagues in this work.

I am also helping to defend our projects. The Lieb House on the New Jersey shore was to be demolished to make way for a “MacMansion”, but Fred Schwartz and Jim Venturi saved it by shipping it away on a barge, up the New York East River and under the Brooklyn Bridge to a new home on Long Island. And Jim Venturi made a film of it. Then the ISI Building was bought by Drexel University for conversion to an architecture school. We watch vigilantly as others alter it. Sadly the Ambler visiting nurses’ building was badly distorted before we could catch it, and changes by the National Park Service to Franklin Court are putting that building at risk. These projects from our early years of practice are suffering the vicissitudes of their long careers. Change must happen and new uses will assure their future. But I must be a zealous and at times fervent defender, fighting for the building, the future, and both of us.

Bob and I have been passionately involved in architecture almost all our lives. Given our ideas, we struggled to find acceptance. And although we eventually succeeded, it was hard, especially for Bob. He has worked energetically in a field that is all about collaboration, but a part of him has wanted to sit in a library and read. So his life has been tense with conflicting aims. Today he relaxes. But I work as hard as ever, because I want to.

However I’m no longer on a frontline, setting down ideas as they grow in the thick of practice.

I learned, during those years, through facing challenging tasks. That’s how the Duck and the Decorated Shed came about. While initiating LLV and rethinking decoration, I watched old factory buildings along the train line as we travelled to New Haven. As a Modernist I adored these buildings but I had always thought the small decorations some had around a front entrance or column capital were a weakness. Perret, after all, had said that decoration always hides a fault in construction. Now I entertained the thought that hiding a fault, because faults are unavoidable, might be beautiful. I began to debate, as well, whether the small amount of openly admitted decoration on these buildings might be less distorting than the twisting and turning of function and structure on Yale’s Art and Architecture Building, which seemed to be done for a decorative aim the architect could not admit.

Noting that Yale’s building in some ways resembled the famous Long Island Duckling (a small commercial structure designed as a duck to sell duck) I wrote an article called “On Ducks and Decoration”.

SM: In 1975 you wrote an important essay titled “Sexism and the Star System in Architecture” that you published later. It was about the difficulty of succeeding for a woman in architecture.

DSB: «So you’re the wife! Are you an architect too?» was a question asked me throughout my career at VSBA and up to today. And I have answered, pointing to Bob: «No, he’s the “architect too”! I am an architect». However this is a problem of being married to a guru, not the one faced by young women as they progress in the field.

SM: At that time women’s rights were at the center of social debate. Today I perceive a new social problem, which is the struggle between generations. In Italy the phenomena is most relevant, it seems that young architects have trouble to take over the previous generation, as there is a sort of “resistance”. What do you think about it?

DSB: There is always a generation problem, and it exists at both ends – I have been at each. But do you believe there is no longer a women’s problem? You’re right – but only in the sense that there never was one. It was always a men’s and women’s problem! And I believe it exists today as strongly as ever. You have not yet perceived it, because as a young architect you are accorded the greatest equality that you will ever know. It gets worse as you proceed, and when it does, you’ll find it is a strong problem. And sadly, because you don’t have a feminist awareness, you’ll think it’s your fault.

Although women start out in practice equal with men, complications set in when they must juggle child-rearing and practice, just at the point in their professional development when seniority brings responsibilities for project management and the need for one hundred percent participation in the studio. Then even if you are brighter than they, the men will go further than you, and you will think: «There’s something wrong with me!»

There are other reasons why men receive preference over women when both reach “the glass ceiling”. And there are reasons – too many to consider here – why architects don’t make gurus of women. And another theory is sometimes offered women: «You have power in your own sphere. Look at the power of the Spice Girls. Why must you compete with men?» This is the age old power of seduction. But where has it got us? As an old feminist recently said: «If the Spice Girls really had power, Dick Cheney, would wear a tutu»!

SM: Thank you very much Denise.

DSB: Thank you Silvia.

Notes

[1] “Learning from Vaccaro”, in Giuseppe Vaccaro, Marco Mulazzani ed., Milan, Electa, May 2002, pp. 66-75. “Working for Giuseppe Vaccaro,” Edilizia Popolare, no. 243, January/February 1996, pp. 5-13.

[2] This would show up even more clearly in the first edition, where we illustrated projects, including our advocacy planning project for South Street Philadelphia, which we undertook in parallel with our LLV study.

[3] Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown, “Architecture as Signs and Systems for a Mannerist Time”, Cambridge, MA, Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2004.

[4] See the VSBA website bibliography for writings by and about us. Also, Denise Scott Brown, “Having Words”, London: Architectural Association, 2009 (AA Words series #4).

Special thanks to prof. Alberto Ferlenga (IUAV), prof. Fernanda De Maio (IUAV), John Izenour (VSBA), Sue Scanlon (VSBA) and Anna Ghirardi (Gizmo) for their co-operation.

Milan, 13.12.2010