by Pedro Guedes

10 January 2011

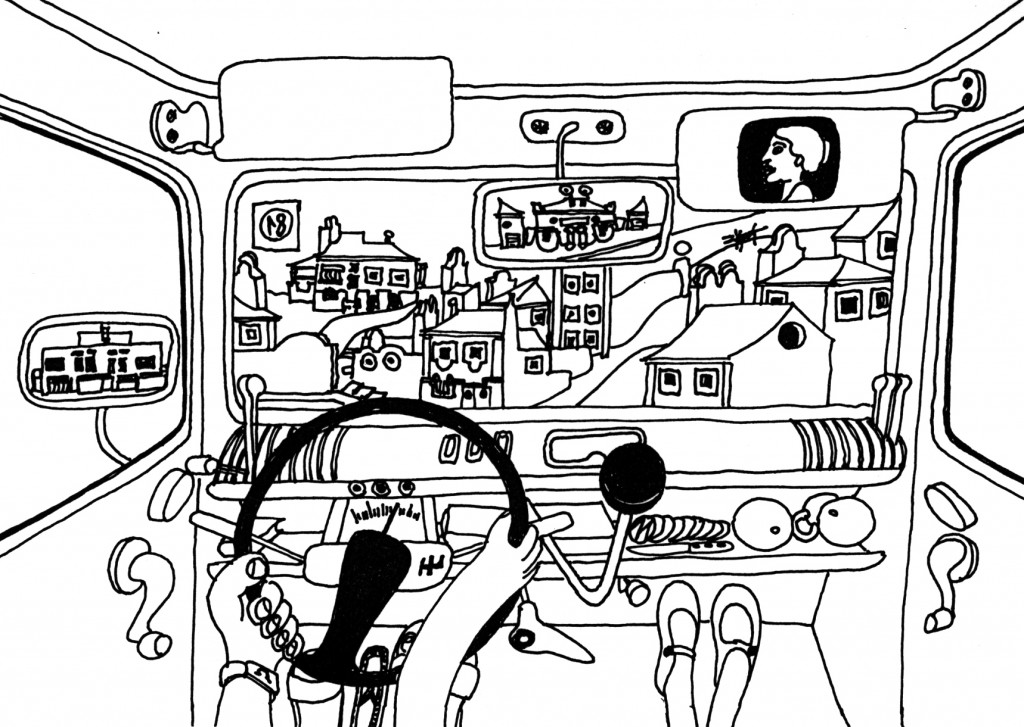

Drawing is the prism through which Pancho understands and creates his worlds. It is the medium through which everything he makes, begins. The prism is the engine of his imagination where the alchemy takes place, releasing images by transforming ideas and hunches into thoughts with some fixity of form and definite presence. Paintings, sculptures, buildings, embroideries, murals and nearly all his imaginings pass through drawing on the way to becoming visible and joining the multiplicity of his creations. Pancho’s prism also works in reverse, taking ideas first thought of by him for painting or anything else, and transforming them into buildings, sculptures or embroideries effortlessly and at times across enormous differences of scale.

As I child, I imagined that this way of working was perfectly natural as Pancho’s office and studio were at home and he was always drawing and performing his magic on paper for projects soon to become something else: occupying a building plot in the city, a shelf at home or in the garden or as another painting on one of our crowded walls. My brother, sisters, myself and our friends were all invited to participate and contribute by scribbling and sketching, seeing what we did admired, treasured and occasionally translated through – appropriation with full acknowledgement – into paintings, sculptures, buildings and embroideries. As a student of architecture in the 1960s in Britain, I realised how unusual this world was from that of fellow architects, particularly when it came to drawing.

The 1960s were a particularly impoverished period for architectural drawing just about everywhere and especially in Britain, where, with few exceptions, very little with character, vision, and speculative exploration of form and fresh ideas was brought into the public realm. Drawings appeared to me to have been downgraded into dry documents whose only purpose was to communicate information, purged of ideas, evocation, personality and any other content.

In Lourenço Marques, Pancho was close to what was happening in architecture, painting and sculpture throughout the world. He had subscriptions to mainstream journals from Europe and the Americas in English, French, Italian and Portuguese and tracked down occasional and ephemeral publications that might interest him, whenever he heard of them. He corresponded with Brazilian colleagues and architects in the American Mid-West about work that resonated with his ideas and established close contacts with people in Great Britain and Europe with whom he built lasting and stimulating links. As a fifteen year-old, Archigram’s pamphlets with their seductive visions of mechanical and ever changing futures were, for me, a highlight of his library. They contrasted with the colonial pre-industrial milieu that surrounded us. Pancho turned being in touch from far away to great advantage, blending engaged detachment with the ability to be inspired by what he had absorbed, interpreted, misunderstood and made his own as it passed through his prism.

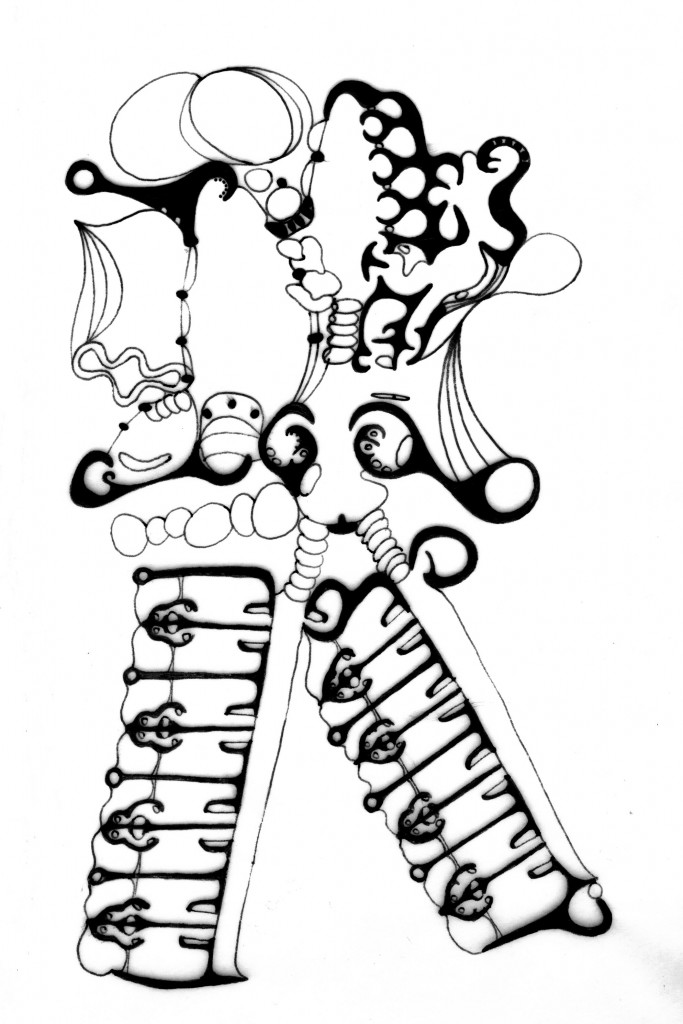

Distances of space and time allowed Pancho to separate himself from the immediacy and apparent urgency of current ideas, placing them on an equal footing with inspiration from other times and places. One of the drawings he most cherished was the pen and ink sketch of the Einstein Tower made by Erich Mendelsohn during the World War I. A reproduction was pinned above his drawing board for over forty years. It is now framed, taking its place of honour among iconic drawings from the 1920s, published in L’Architecture Vivante (1923-1932) as coloured lithographs during the heroic period of the Modern Movement. The Mendelsohn sketch helped confirm the possibilities of form that Pancho brought to life in the Swazi Zimbabwe [Curvaceous residential building in Western Swaziland] and other related projects. Similarly, Paul Klee’s drawings and sketches were particularly welcome guests in Pancho’s prism. Klee’s playfulness, inspired and masterful meanders of line came out in murals, drawings and most recently in a series of angel sculptures in translucent plastic and metal. Picasso’s studies for unrealised sculptures helped generate the vocabulary of forms that characterise aspects of Stiloguedes buildings and sculptures, while his work with two-dimensional line was transmuted into the wonderful welded steel children’s climbing frame that Pancho made for the Zambi Restaurant.

Working through drawing to transmute, appropriate and advance the work of others is a characteristic of Pancho’s method. Aspects of Louis Khan and Frank Lloyd Wright join those mentioned above as acknowledged contributors to Pancho’s vocabularies together with the 16th century topographical painter Duarte d’Armas; Michelangelo’s drawings for fortifications run alongside countless others from the mainstream as well as the forgotten corners of Western architecture and art across the ages. He makes all of them his contemporaries and converses with their work as if they had just left the room.

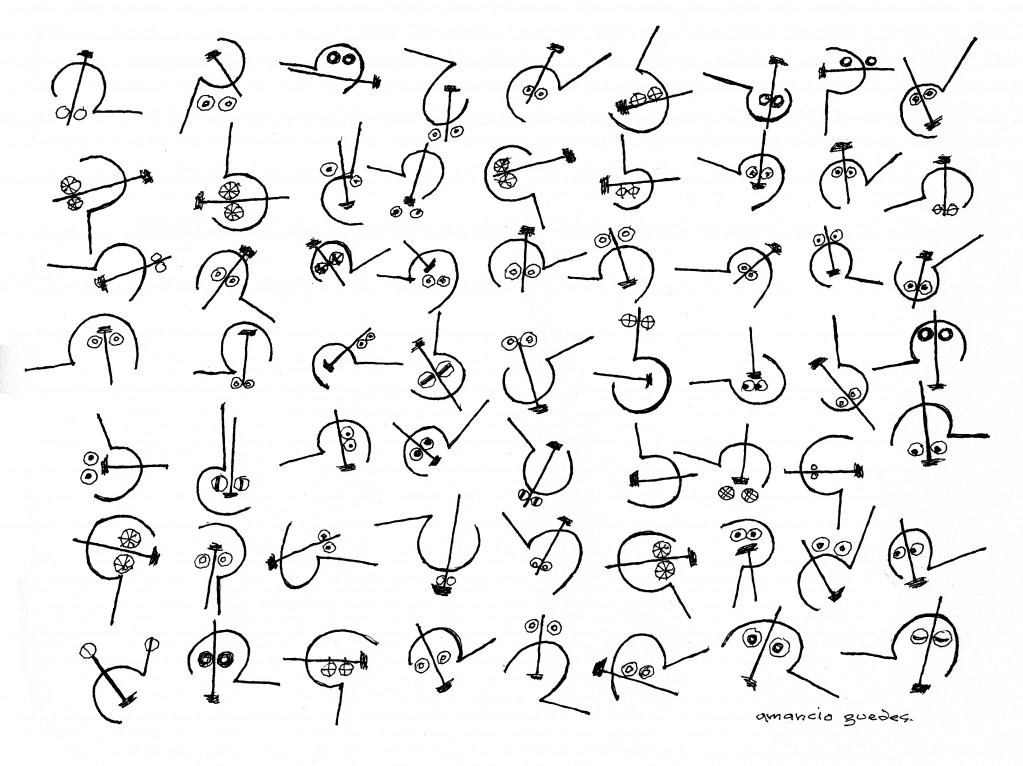

Pancho uses drawing to translate and incorporate what he chooses into his expansive and growing lexicon of possible responses. But in the multiplicity of Pancho’s discourses, appropriations seldom survive as direct quotations. They are broken down into their fundamental graphic, stylistic strategies and implied plastic elements to emerge reassembled and fused with allied ideas to become parts of one or several of Pancho’s personal syncretic languages, some spoken in smooth, suave and sophisticated accents while others remain in proudly crude and direct argot.

Pancho’s prism gained its acuity and inclusiveness in Africa where Western reductive thinking coexisted with many other ways of seeing the world. His early drawings have hints of these tendencies, but they became stronger and stronger as other world-views and individual interpretations entered his spectrum through the work of people and cultures in flux. I remember accompanying him on a visit to remote Ndebele kraals [Group of houses or the social unit that inhabits these structures – Editor’s note] in South Africa where the women made marvellous buildings with complex mud courtyards, ordered by elaborately painted forms and integral furniture. I was eleven years old and had my first camera. We both took photographs and he made bundles of sketches and measured drawings. Talking to people about their work and recording it became a regular habit for Pancho wherever he travelled. He collected traditional ritual sculpture, not bought from dealers but from those who had used and made them. He sought out, sketched and amassed drawings, graffiti and embroideries made by people whose recent transition from rural to city life allowed them to gain insights with fresh eyes and record them with fascination and intensely individualised character. Pancho engaged with enchantment, wonder and magic of these experiences recorded in the drawings of his disparate collection.

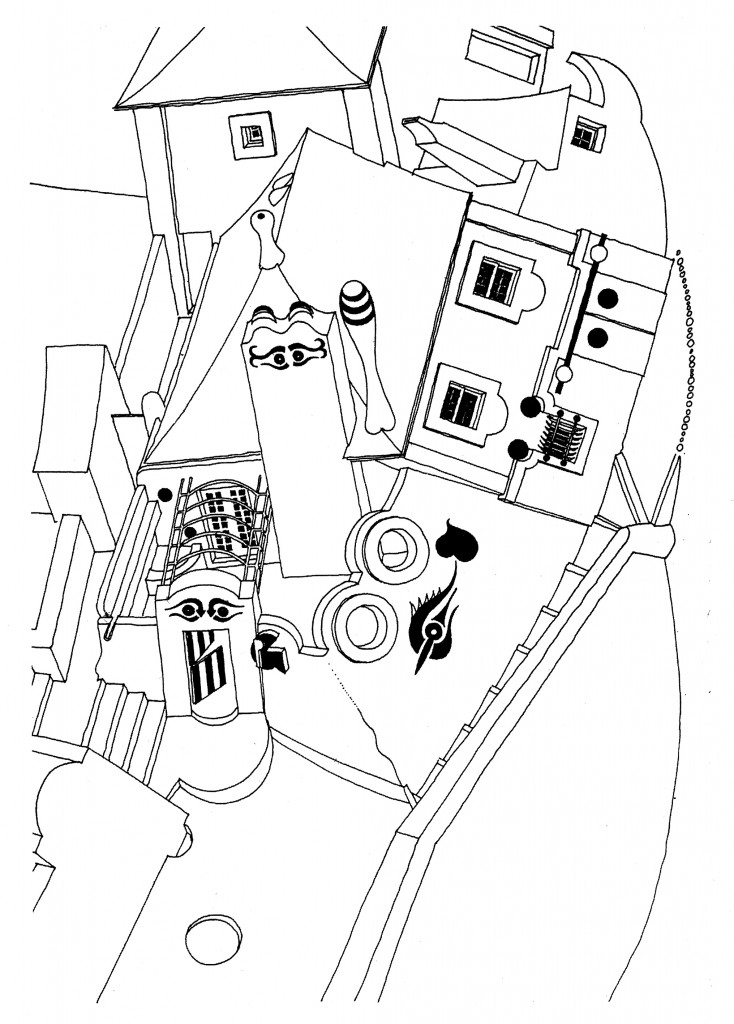

Pancho absorbed other influences through drawing by meticulously recording vernacular structures throughout Mozambique as well as early colonial buildings from the 16th century onwards that blended more ancient Arab traditions with Indian and Portuguese influences. Mouldings, plan strategies and building forms from these sources passed through Pancho’s drawings to join and enrich the several vocabularies of his disparate architectures. Minute components of these buildings such as locks and other items of ironmongery yielded up forms and combinations of parts that passed through the prism and emerged at different scales with faint but definite memories of their origins. He worked in the same way with recollections, images and fleeting records of buildings in Portugal, inspiring groups of domestic buildings in Mozambique in the 1950s to be followed by an enriched and more playful engagement with similar themes when he first engaged with building for himself in Portugal in the 1980s. Treasured bones of turtles, contorted mangrove roots, shells and pebbles from riverbeds and beaches joined artefacts from which ideas, forms and shapes could be coaxed and found.

Pancho’s early drawings for architectural projects include formally rigorous set-up perspectives, but these were followed by far looser renderings in pencil that evoke the spirit of his idiosyncratic buildings. These drawings, mostly executed in pencil on cheap butcher’s paper, when time was short, have great flair and confidence. They capture the atmosphere of the architectures of his invention in tune with a sub-tropical climate. Later drawings are more deliberate and formal and were built up in several stages before being traced freehand in ink. Sketches and studies for paintings and sculptures that survive, have the more private and exploratory character, but share some of the stylistic attributes of the earlier drawings for buildings.

Projects are not abandoned once they have been built. Many come back to drawing for repairs and improvements and take up a separate life on paper. Some of his favourites return regularly for transformations while others are raided for useful parts and ideas that can enrich other works. Very little in the œuvre has finality and completion is viewed as a passing stage. Sculptures and paintings are vulnerable to complete overhaul, with some emerging unrecognizable, decades after they were first completed. For people, other than Pancho, familiar with the works, these radical changes are often annoying and disappointing – I know that my mother Dori found these transformations particularly exasperating. Drawings are the survivors because they are bypassed by these impulsive episodes. When Pancho is urged to change something in a drawing, he simply makes another one so the work continues to exist simultaneously in several of its states of becoming.

Alongside, Pancho had to complete mountains of drawings so that buildings could be built. He working late into the night when the phone would not ring, making almost all the complete sets of working drawings himself. On nearly every job, drawings from engineers were redrawn to make them part of the group, so that they could share the drawing style and paper size. All sheets for a particular project were cut from roles to a size to suit the proportions of the plans or, in the case of tall buildings, the sections and elevations and every sheet was hand-lettered with a favourite font of the time. Pancho worked fast and drew in pencil with great precision. He could put together a complete set of drawings over a longish weekend and then move onto a building in an entirely different style without the need to warm up or catch his breath. For the more intricate projects such as the Euclidian Palaces of the late 1960s, the plans and details with their meticulous dimensioning become quasi-abstract documents that anticipate thicknesses of plaster and the lining up of surfaces in complex three dimensional junctions of visible structure without the various layers being drawn. Consolidated experience and a close understanding of the skills, available together with a complete knowledge of the possibilities offered by local construction techniques made it possible for Pancho to bring many of his building projects to life.

Where conventional building or regular documentation would not be helpful, Pancho was inventive in adapting the way buildings were drawn to make their execution possible. After he persuaded the Swiss Mission to entrust their foreman Muchlanga with the building of schools and other structures, Pancho developed a system of making drawings that could be interpreted without the need for reading skills. Muchlanga could set out the buildings and determine heights by counting the cement blocks that formed the basis of the construction. These were clearly shown on all the drawings and helped determine the sizes of other components such as the timber roof trusses. In these austere buildings where every constructed surface was visible, the discipline of the drawing technique helped ensure that the buildings had a unique character in tune with Muchlanga’s superb skills at realising them within the limitations available.

Under the paint and plaster of nearly every building built under Pancho’s supervision there are wonderful explanatory sketches that will never be seen again. They were made to clarify details or explain ways of resolving unforeseen problems. Accompanying Pancho on site visits was a great lesson. I cannot remember any formal site meeting with notes and minutes or with issues to be resolved at a later date. Drawings and sketches on walls came to the rescue and on the next visit, what had been sketched was likely to have been built.

Pancho’s paintings sculptures and buildings are the formal face of his work. Behind them there are the drawings that brought them to life and those that continue to question, subvert, undermine and improve upon what was fixed with some fleeting finality. The drawings are the life of his work.

[first published: Guedes, Pedro. ‘Os Desenhos de Pancho – Pancho’s Drawings’ in, Guedes, Pedro (ed.) Pancho Guedes – Vitruvius Mozambicanus, Lisboa: Museu Colecção Berardo, 2009, pp. 262-267]

http://espace.library.uq.edu.au/view/UQ:196173