Visitor Centre Building, Twyfelfontein, Namibia 2005-2007

Funding: European Union

Client: National Museum of Namibia

Architects: Nina Maritz and Dennis McDonald

Engineers: Volker Uhrich Consulting Engineers

The building in the landscape

Huge slabs of rock lean against each other to create narrow vertical slits and curved overhangs form shallow caves in the boulder-strewn landscape of Twyfelfontein. The original inhabitants would have used these rocks and caves or brushwood structures, clad with grass bundles, for shelter. To create a modern building that merges with the terrain, elements of the landscape were influential in determining the form and construction methods.

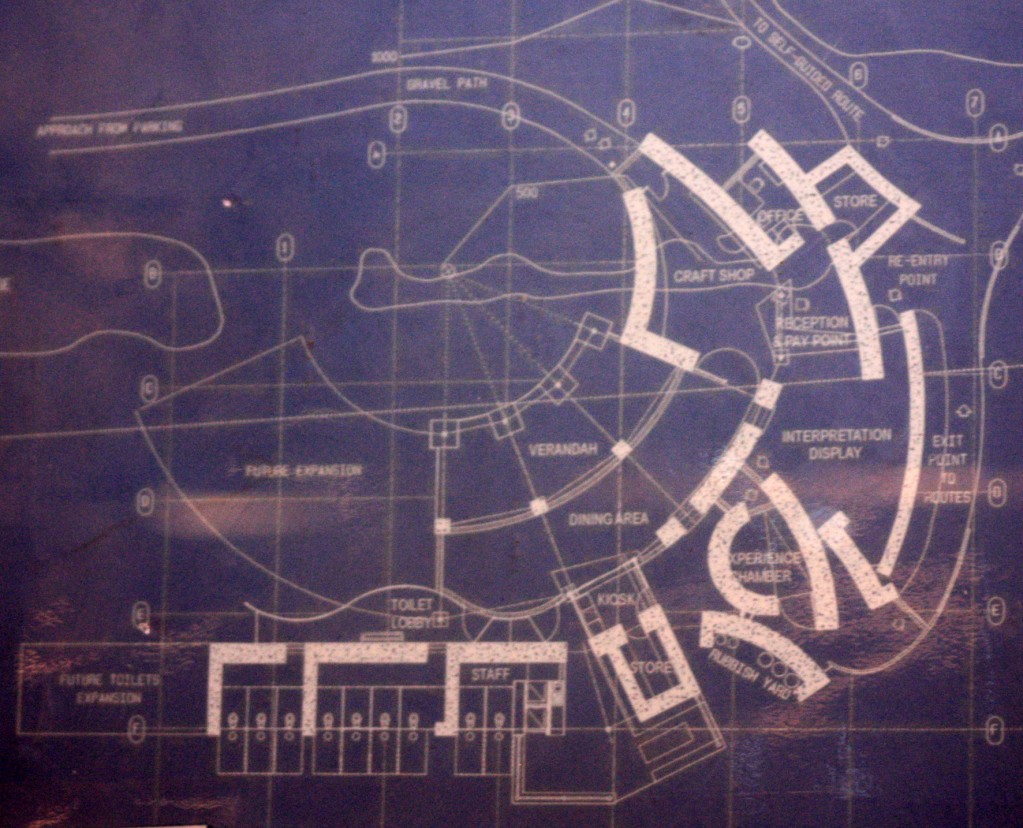

Inspiration for the curved forms and ‘armoured’ cladding was drawn from animal skeletons, insect carapaces and antelope spoor-shaped mopane tree leaves. To prepare the visitor for engagement with the rock engravings, the building conducts you through a series of spaces that refer to the different stages of trance ritual. The plan itself is based on one of the San metaphors for the third stage of trance: an antelope with a curved back.

Recycling

Hand-packed wire gabion-baskets of local sandstone, filled in with recycled rubble from demolished structures, form the walls.

The roof’s steel structure is covered with ‘tiles’ made by cutting up recycled oil drums, also used for screen walls and signs.

New roofing materials with their high embodied energy would have looked out of place in this environment, and also could not achieve the bi-directional curves required for the shape of the building. Recycled and rusted steel helps the building blend in visually with the surrounding red and brown rock. The floor is of Namibian-made clay bricks packed on leveled, compacted sand.

Cement was avoided as it is difficult to get rid of after demolition and has high ‘embodied energy’, the energy used in its manufacture. High embodied energy contributes to global warming. By using recycled materials, the building itself has lower embodied energy and is thus more sustainable.

How the building keeps cool

The roof is insulated with a ceiling of reed mats that were cut and woven in Otjiwarongo as part of an employment project. Trapped air in the reeds helps reduce radiation from above. Between the reeds and the drum roofing, an additional layer of silver foil also reflets the radiation from above. The building curves around an open space facing north, so that on winter mornings, the low rays of the sun can warm the interior. In summer, the sun is much higher overhead and the roof shades the seating areas. The thick stone walls soak up heat, helping to keep inside spaces cool, and the high roof shapes with openings at the top channel rising hot air to the outside.

Precious water in a deserta

Water is delivered by trailer once a week and hand-pumped to the storage tanks.

It is only enough for hand washing for visitors and showers and drinking water for the staff. Water is no longer pumped from Twyfelfontein spring to the building as it was beginning to run dry from over-use. In order to keep the spring intact and to retain this lifeline for a host of wildlife, it is necessary to supply the visitor centre’s water needs from outside. The dry compost ‘Enviro-loo’ toilets save water and avoid sewerage disposal that can cause pollution of the fragile environment.

Was this expensive?a

The 500m2 building was built as a cost of about N$ 1200/m2, compared to current conventional building costs of about N$ 4000/m2 (2005). The low cost was due to alternative design and construction methods, as well as the use of recycled materials.

Powered by the sun

A ‘homemade’ solar system is used to run the office equipment. The kiosk freidge and freezer use bottled LPG gas. Why was conventional electricity not installed? Not only is connection to the electricity grid too expensive, it is also less sustainable as Namibia’s power is mostly generated in coal-fired power stations in South Africa. Solar and gas are thus better for the environment.

12 dicembre 2011