by Marco Biraghi

Talking about a Milanese identity of modern architecture – and not, more generically, about an identity of Milanese modern architecture – means recognizing not just a local value, though that is significant and important, but also a leading role on the international scene of the architectural output of the city after World War II.

Talking about a Milanese identity of modern architecture – and not, more generically, about an identity of Milanese modern architecture – means recognizing not just a local value, though that is significant and important, but also a leading role on the international scene of the architectural output of the city after World War II.

The most outstanding characteristics of Milanese modern architecture cannot be identified by means of theory, but instead can be accessed directly “in the field,” in the living body of certain works that – though in a unique, unrepeatable way – establish that identity in a lasting manner. Better than all others, perhaps, an initial, valid synthesis is supplied by the complex for offices and apartments on Corso Italia by Luigi Moretti (1949-55): a project that is modernly orthodox from a structural and linguistic standpoint, yet extraordinarily inventive and courageous in the way it reformulates the syntactic connections between architectural elements and above all between constructed volumes, which reach the point of breaking up the traditional street frontage. The result is a modernity that forcefully stands out from any previous or contemporary precedents, for the high degree of awareness and nonchalance it displays; an awareness and a nonchalance that are signs of an elegance that is far from being skin deep, but is firmly rooted and metabolized; a lifestyle more than “styling” in the formal sense. It is a physical, three-dimensional translation of that attitude of leaning forward, of surpassing what is already familiar, at times taking real risks, that is a part of the entrepreneurial spirit of Milan in those days, a city of work with an often forcefully innovative character.

The same lineage also very clearly includes the Torre Velasca (1951-58) by the studio BBPR and the Pirelli tower (1956-60) by Gio Ponti, Pier Luigi Nervi and others: the bifrontal – if not two-headed, even – emblem of the Milanese desire to take part on the international scene, but at the same time of the proud desire to play a leading role there, not as a mere extra. On an equal footing, other buildings – though without a major urban role or a functional purpose of particular importance – belong to these ranks, built by excellent professionals like Luigi Caccia Dominioni, Ludovico Magistretti, Mario Asnago & Claudio Vender, Vito & Gustavo Latis. This is the high-quality, eminently civil development that sets Milanese output apart, especially from the 1950s to the 1970s; buildings that are never guilty of excessive luxury, and seem in fact to derive their “class” more from constraints than from unlimited possibilities. One exemplary case is the apartment building on Piazza Carbonari (1960-61) by Caccia Dominioni, whose irregular profile – which together with the apparently random position of the openings gives the building an almost abstract look, and therefore an easily recognized individuality – is actually the result of maximum exploitation of the volume permitted by building regulations.

It should come as no surprise that in a city like Milan (one of whose most famous and highly acclaimed buildings was nicknamed, by popular demand, “Ca’ brüta” or, literally, the “ugly building”), the “virtuous” situations usually arise from necessity, rather than favorable conditions from the start. It is precisely this ability to make circumstances into opportunities to build that constitutes one of the characteristic features of the Milanese identity. The Monte Amiata residential complex (1967-74) by Carlo Aymonino and Aldo Rossi, in the Gallaratese district, epitomizes this approach: in spite of its far from advantageous location in a peripheral zone of the city – and, in fact, precisely because of that location – the project by Aymonino and Rossi sets out to become the banner of a city radically revised in its class relations, in which the inhabitants of subsidized housing are granted an unprecedented dignity and in which the relationship between the historical center and the outskirts is reformulated in favor of the latter, raised to the status of a new peripheral center.

Though starting with utterly different premises and results, it is also easy to find signs of a Milanese identity in the architecture of the 1980s and 1990s. Precisely this Lombard city, with the nickname in that period of “Milano da bere” (roughly “swinging Milan”), became the center of a complex political-administrative system with repercussions that often went beyond the boundaries of the law; this phenomenon had a major impact on the construction sector as well, where a building like the Nuovo Piccolo Teatro (1979-98) by Marco Zanuso – which paradoxically set records for both modesty and waste – can be seen as a typical example.

Even at the start of the 21st century, in spite of significant variations in the overall economic, political and social framework, and with the tensions to which it is subjected, the Milanese identity in architecture continues to be quite identifiable. While the rise of many skyscrapers, also in zones very close to the historical center, has lagged behind similar operations in other cities in Europe and America, not only in terms of construction but also in terms of planning, it still points to the open character of the Milanese mentality, always ready to absorb input from the outside world. The various languages that intertwine in the works of architecture in Milan over the last decade (the new Lombardy Region headquarters by Pei Cobb Freed & Partners, the Unicredit tower at Porta Nuova by César Pelli, the buildings of the Maciachini Center by Sauerbruch Hutton, the CityLife complex on the area of the former trade fair facility, with works by Zaha Hadid, Daniel Libeskind and Arata Isozaki, Fondazione Prada by OMA, Fondazione Feltrinelli by Herzog & de Meuron, just to name some of them) are precisely the mirror of this pluralistic, cosmopolitan culture.

This globalized and very “image-conscious” Milan that is even all too willing to let itself be seduced by the architectural jet set, allowing itself to be used like a board game on which to position pieces by famous names, has been countered in recent years by a Milan that pays closer attention to its own heritage (see the buildings by Cino Zucchi at Nuovo Portello, 2001-11, or at Porta Nuova, ????-??), capable of recovering forms of “resistance” and of cultural and social survival; “islands” of meaning, alternatives to the established, dominant logic; less showy “islands” but ones that are more effective and intense than their more vertical counterparts, and offer further possible interpretations of the way the city is conceived and experienced. We can mention the Casa della Memoria (????-15) by Baukuh, or the Shoah Memorial (2004-15) at track 21 of the Central Station by Guido Morpurgo & Annalisa De Curtis Associati, as examples of Milan’s desire not to lose “pieces” of its identity. A complex, mutable identity that nevertheless, at its core, has always had the ability to reconcile a strong drive towards the new with an equally pronounced respect for that balanced, measured “character,” endlessly concerned with maintaining its aplomb, that belongs to the Milanese tradition. As a whole, a reserved bearing that even the construction of modern Milan has managed, somehow, to safeguard and reflect.

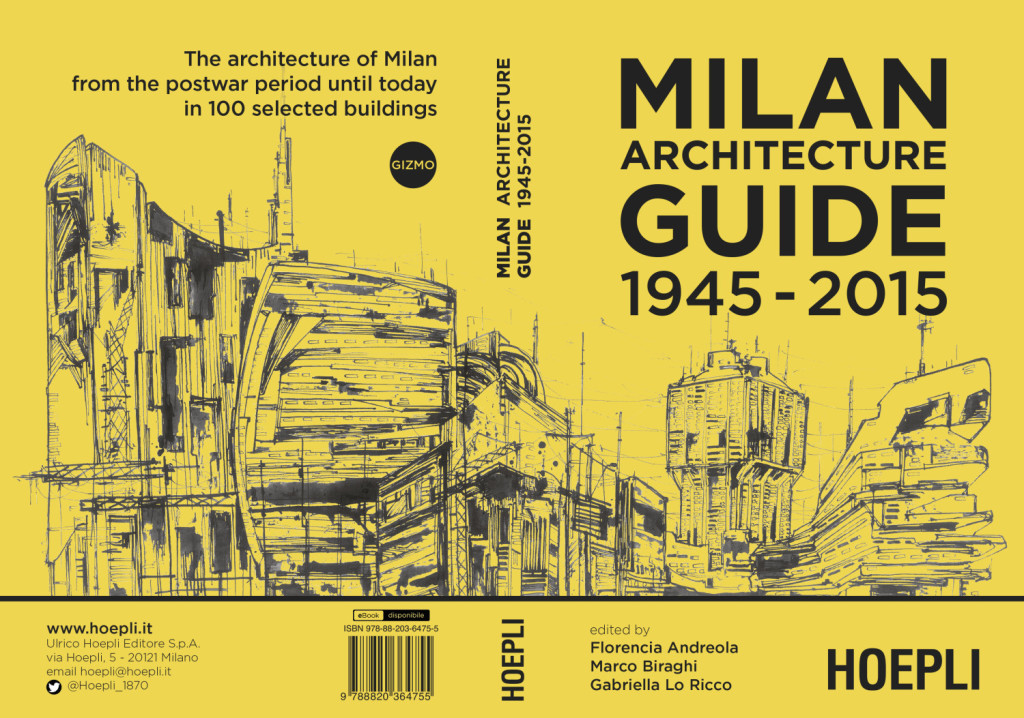

Milan Architecture Guide 1945-2015

edited by Florencia Andreola, Marco Biraghi, Gabriella Lo Ricco

HOEPLI, Milano 2015

Acquista su www.hoepli.it

April, 2015