by Giulia Ricci

Pt. 1: A complex environment

Since its foundation, Zingonia has been a city of conflicts.

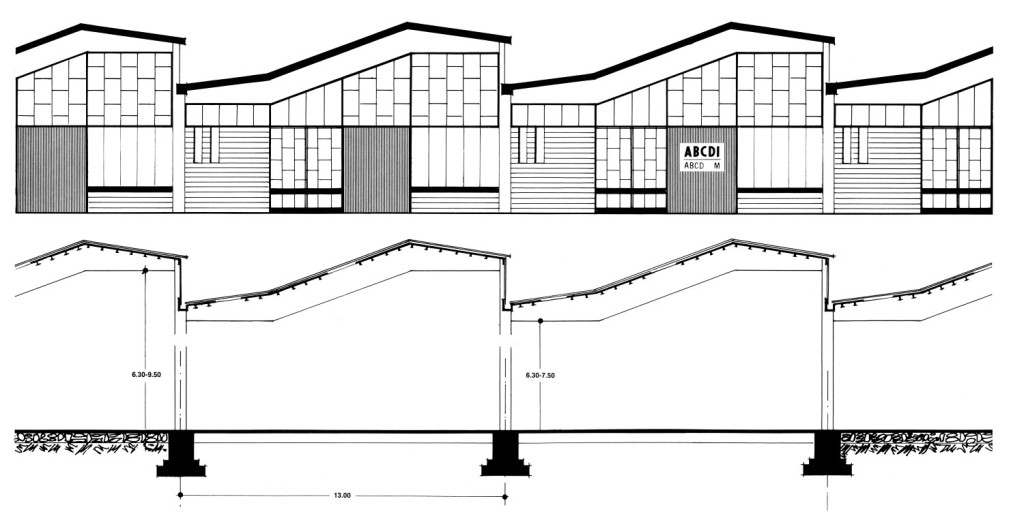

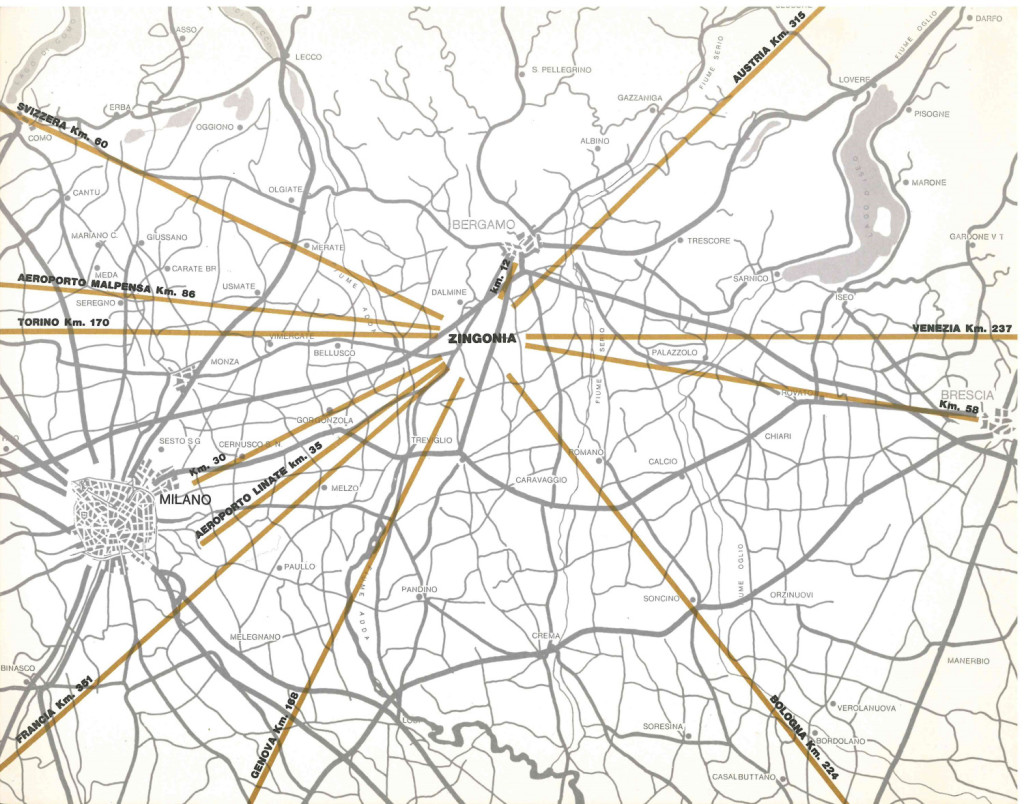

This planned city is sited in the Padan Plain, on the trajectory of a big set of infrastructures connecting Venice, Milan and Turin. The whole plain is a strategic area, characterized by urban sprawl in combination with industry as leading sector. Zingonia’s proximity to Milan, that at that time was considered the main productive industrial core of the whole country, gave to this operation the connotations of a promising investment: one of the aims of its investor was to eliminate commuting for workers, so that they could live and work in the same place.

Z.I.F., Zingone Iniziative Fondiarie, owned by Renzo Zingone, bought the future building sites in 1960, in a territory that was, and still is, divided in five different municipalities: Ciserano, Verdello, Verdellino, Osio di Sotto and Boltiere. The operation conduced in Zingonia took advantage of the national law 1169/65, which assigned low interest mortgages to developers building in depressed areas.

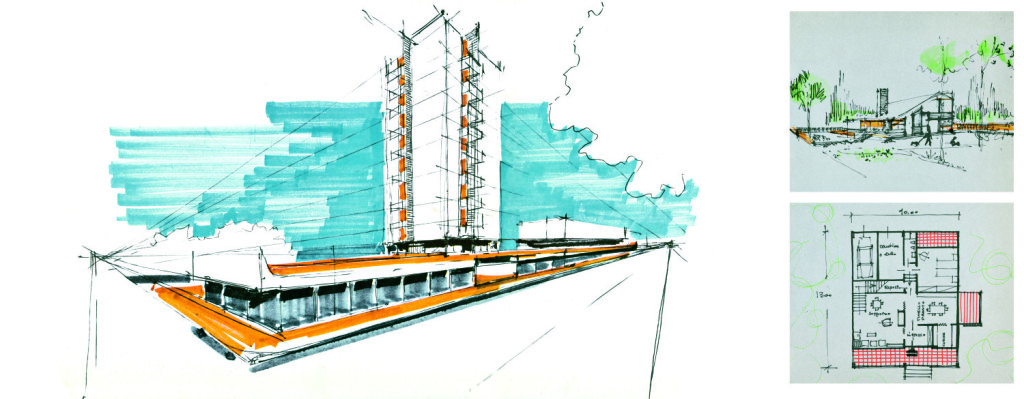

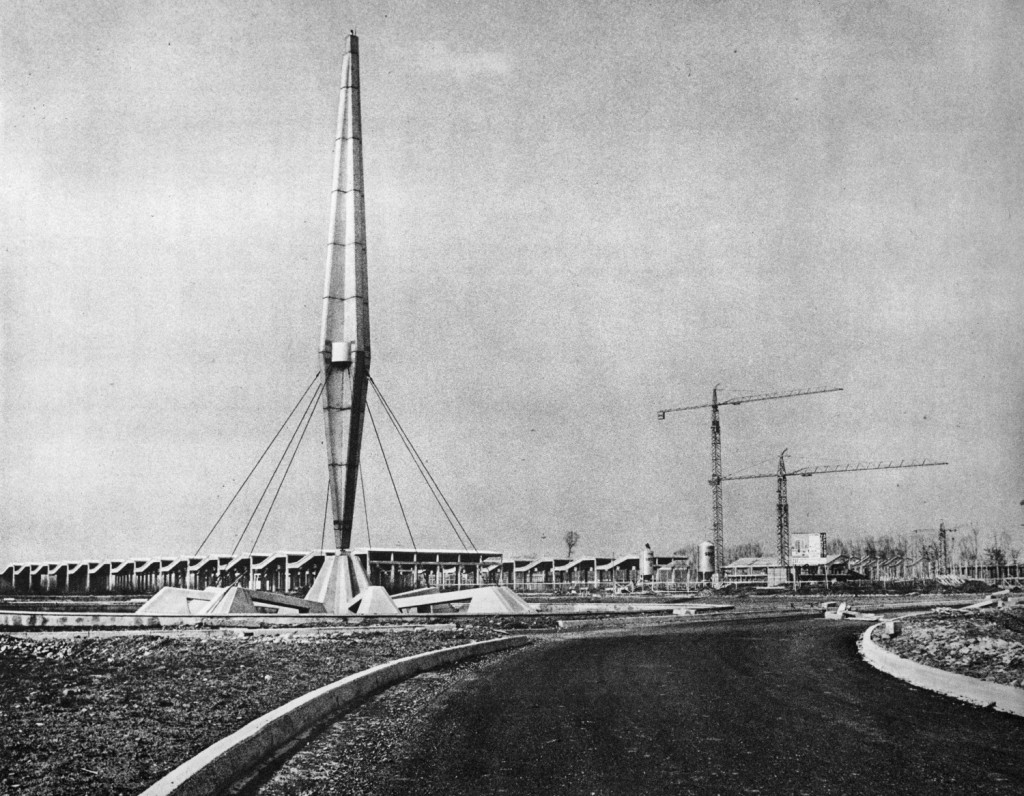

The design was made by Franco Negri in 1964 and the construction started in the same year. Renzo Zingone and Franco Negri had already worked together for a similar project, a new district in Trezzano sul Naviglio, named Quartiere Zingone.

Zingonia was designed following the principles of the Charte d’Athenes (1933) and was inspired by Lucio Costa’s plan for Brasilia.

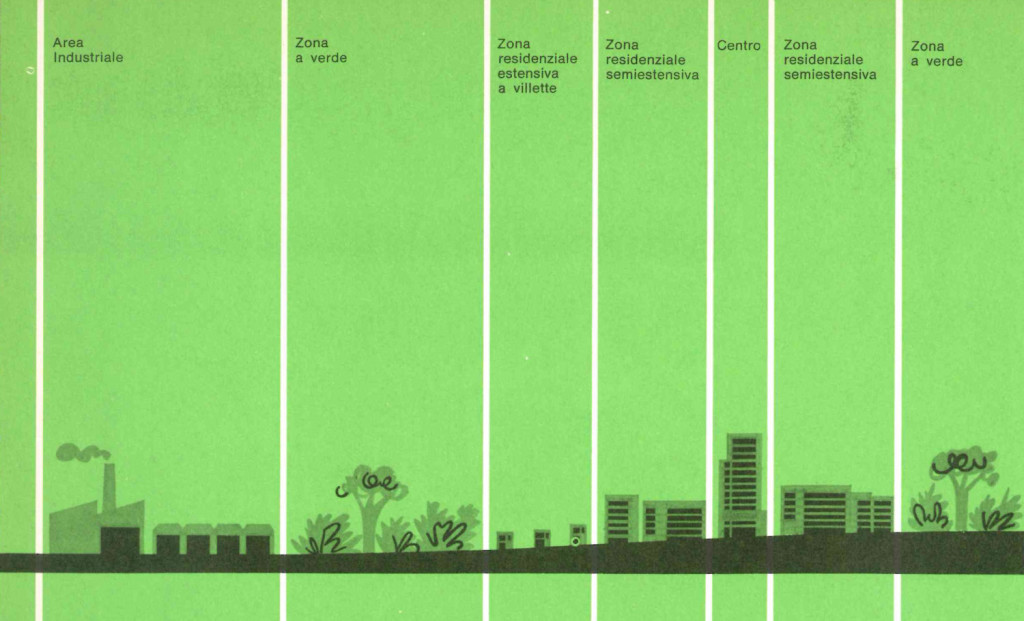

The arterial roads were the framework for functionally segregated areas, in a car-oriented urbanization system. Open spaces and sport facilities played an important role and were meant to physically divide industries and residences, new and old neighborhoods and social classes (Sinatti, 2006). Zoning is to be understood as a tool to separate functions inside of a built environment but also to shape social segregation.

The decline of the city of the future took place when the city itself was still very young, in the 1970s:

Renzo Zingone had difficulties in maintaining a steady profit and this made him return back to South America where he had started his career. The administrative division in five municipalities implied long-term negotiations. In addition, the 1970s economic slowdown weakened the city’s industrial area. A big part of the public facilities that had been planned were not built; as a consequence, immigrant families preferred to live in the pre-existing towns, which provided better and more comprehensive services (Ruggeri, 2010). This eventually turned Zingonia into a transitional space.

This city was not designed to become a walkable city. As in the case of Brasilia and many other modernist cities, it was conceived following the principles of the sistema rodoviarista; this means that cars are intended to be the dominant mode of transport.

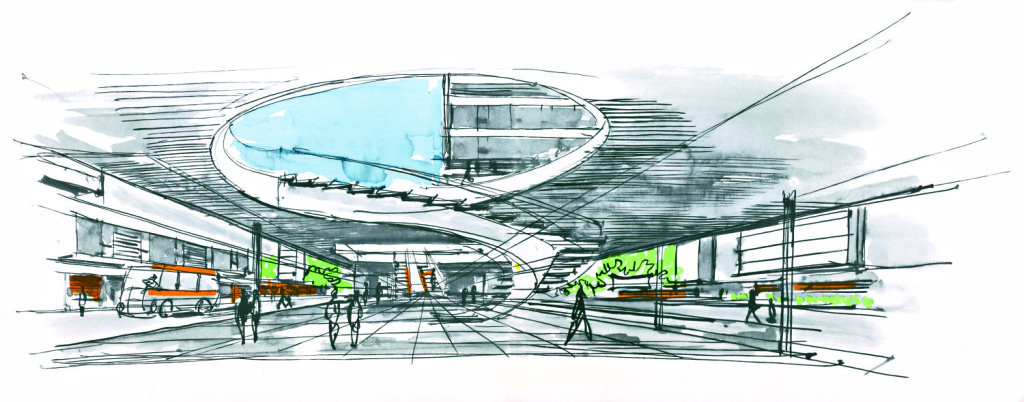

Zingonia, as it was designed by Franco Negri and Renzo Zingone, has never been built. The business center was not built, as many other facilities and infrastructures. Driving through its streets one can feel that the borders between residential and industrial areas are not defined; in addition, it is hard to meet other people in public spaces because such spaces are scarce and buildings seem to stand in a placeless atmosphere.

Immigration as a mainstay

The whole operation relied on the strong potentials of the rising industrial area of the city which created job opportunities and therefore attracted a big number of immigrants.

In those years, 15 million people moved from the South of Italy and the region of Veneto to the North-West in search for jobs, especially in the area of Milan where many flourishing industries were sited.

Zingonia soon became an attractor for those seeking a job. The provenance of those who came with the first wave of immigration followed the national tendency.

Most of the people that Gizmo has met in Zingonia came from the South of Italy indeed, and their stories were about a very dynamic situation that they found in Zingonia as they arrived: it was very easy to get a job in just one day.

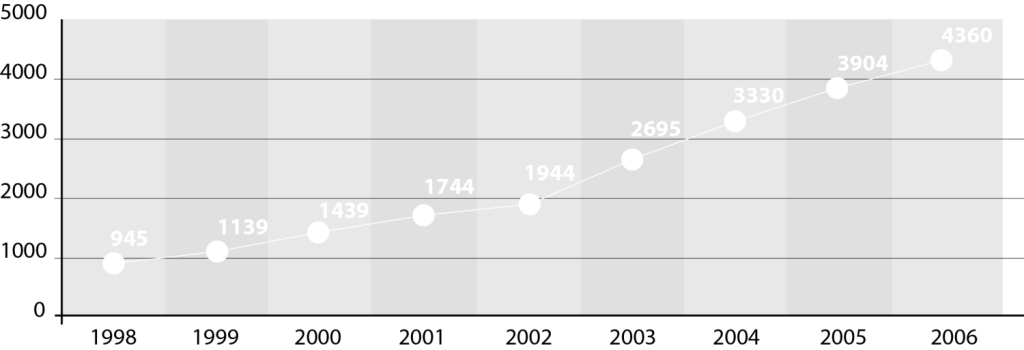

From the 1980s, a new big wave of immigration came to Italy from extra-European countries and those people were employed in Zingonia’s industrial compartment. Following the national trend, the immigration flux became even greater in the 1990s-2000s and Zingonia saw its immigrant population increasingly grow (I1).

The data shown in the graph below reports the different ethnical groups present in Zingonia: in most of these groups we can also find a great disparity in numbers between the sexes.

A single immigrant man is often perceived as dangerous. However, most often these men migrate to Italy (or other European countries) to work and send money to their hometowns and families, while women stay in the mother countries to take care of the family.

(I1) Growth of the immigrant population from 1998 to 2006. (Sinatti, 2006)

The different groups act very differently in this environment: while the Senegalese and the Pakistani communities organized some social spaces and activities as the Daara (a religious and community center) and the Pak cricket club of Zingonia, other groups are not reported to do the same. Those spaces and activities are mainly meant to be for their community but they also organize events that are open to the rest of the population, seeking for more integration.

Moreover, because of the high concentration of Senegalese immigrants, they decided to elect Zingonia as the venue for the Senegalese association for the province of Bergamo.

The Senegalese and the Pakistani communities also work as reference points for the new immigrants who need support as they arrive in Italy. These new immigrants join these communities as they arrive in Italy and are helped to integrate and to get oriented in the new country. In this way Zingonia confirms its role as a transitional space.

(I2) The main immigrant communities present in the territory of Zingonia. (Sinatti, 2006)

The defective configuration of the physical space of the city and the principles that were followed in the design process are not the only causes that brought Zingonia to this situation of decay.

In addition to the reasons connected to design decisions or inaccuracy, administrative and social problems must be considered in order to achieve a comprehensive understanding of the dynamics that such a context implies.

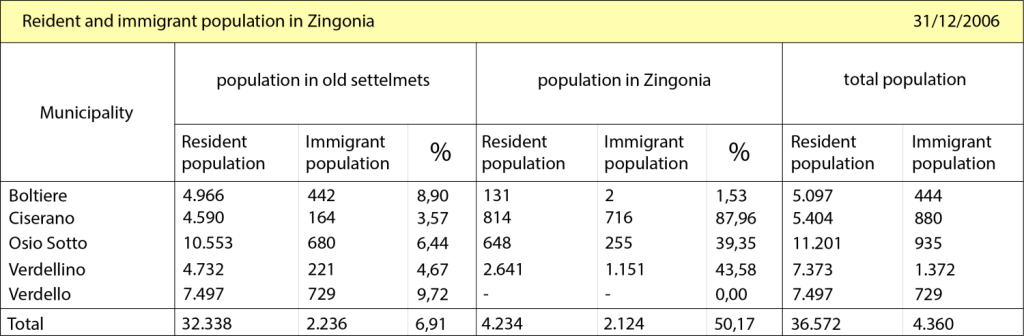

Zingonia’s territory is divided in five municipalities: Osio Sotto, Verdello, Verdellino, Ciserano and Boltiere. The immigrant population is unevenly split in this territory (I3) and this has different effects: immigrants are concentrated in Zingonia, somehow out of sight of who’s living in the town centers. Zingonia is perceived as a lawless and dangerous place because of the immigrant population. This regards especially the area of the six towers named Athena 1, 2, 3 and Anna 1, 2, 3, which are located in the municipality of Ciserano on one of the main streets of access to the city, surrounding Piazza Affari.

(I3) Distribution of the immigrant population in the territories of the five municipalities and in Zingonia. (Sinatti, 2006)

Media, politics and imaginary

In the imaginary of those living in the area these towers are the epicenter of the urban decay.

While it cannot be denied that there are episodes connected with prostitution, drug trades and illegal immigration, on the other hand there is a strong process of stigmatization, via local newspapers, of a city that never integrated with its context, that was always felt as something external, something which was imposed and needed to be alienated from the original towns as well as from their citizens.

In this situation, private interests and political forces are manipulating the public opinion in order to avoid any resistance to their will to demolish the six towers of Ciserano. This, of course, includes an expropriation process.

The province and the municipalities are working on the new master plan: as a matter of fact, the city is located on the trajectory of a large-scale infrastructural project, which includes the international line of high speed trains (TAV) and the Pedemontana highway.

No other strategy was envisaged as a possible solution. Since Zingonia was founded, many attempts were made in order to overcome this administrative fragmentation, including a referendum for the creation of a new municipality of Zingonia (in the’70s) and an Inter-municipal consortium that closed in the 1980s.

The resolution of its social issues would require an independent administration for Zingonia, but the other municipalities see this territory as strategic: The many dynamic industries and activities in the industrial area of Zingonia generate an important revenue for them.

It thus seems that the municipalities are exploiting the city’s still flourishing industrial compartment for their own profit, but they are not interested in solving the issues connected with immigration. On the contrary, they take advantage of the condition of segregation of the immigrant population. This dynamic produces a lower concentration of the immigrant population in the centers of the five municipalities than the regional average. The immigrant population is concentrated and segregated in one point: a positive side effect of a very remunerative practice of carelessness.